Previously we stated that success might be a cube rather than a point. If we stay within the cube but miss the point, is that a failure? Probably not! The true definition of failure is when the final results are not what were expected, even though the original expectations may or may not have been reasonable. Sometimes customers and even internal executives set performance targets that are totally unrealistic in hopes of achieving 80–90 percent. For simplicity’s sake, let us define failure as unmet expectations.

With unmeetable expectations, failure is virtually assured since we have defined failure as unmet expectations. This is called a planning failure and is the difference between what was planned and what was, in fact, achieved. The second component of failure is poor performance or actual failure. This is the difference between what was achievable and what was actually accomplished.

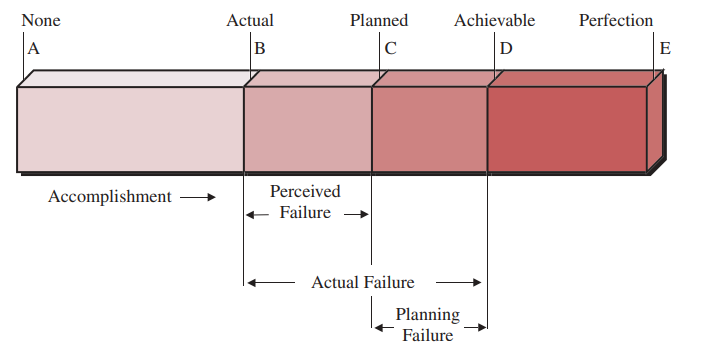

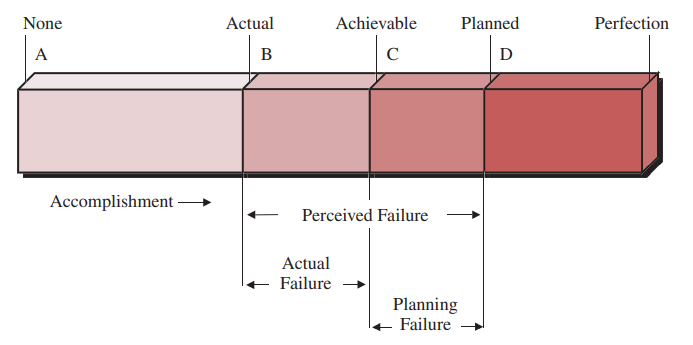

Perceived failure is the net sum of actual failure and planning failure. Figures 2–15 and 2–16 illustrate the components of perceived failure. In Figure 2–15, project management has planned a level of accomplishment (C) lower than what is achievable given project circumstances and resources (D). This is a classic under planning situation. Actual accomplishment (B), however, was less than planned.

A slightly different case is illustrated in Figure 2–16. Here, we have planned to accomplish more than is achievable. Planning failure is again assured even if no actual failure occurs. In both of these situations (over planning and under planning), the actual failure is the same, but the perceived failure can vary considerably.

Today, most project management practitioners focus on the planning failure term. If this term can be compressed or even eliminated, then the magnitude of the actual failure, should it occur, would be diminished. A good project management methodology helps to reduce this term. We now believe that the existence of this term is largely due to the project manager’s inability to perform effective risk management. In the 1980s, we believed that the failure of a project was largely a quantitative failure due to:

● Ineffective planning

● Ineffective scheduling

● Ineffective estimating

● Ineffective cost control

● Project objectives being “moving targets”

During the 1990s, we changed our view of failure from being quantitatively oriented to qualitatively oriented. A failure in the 1990s was largely attributed to:

● Poor morale

● Poor motivation

● Poor human relations

● Poor productivity

● No employee commitment

● No functional commitment

● Delays in problem solving

● Too many unresolved policy issues

● Conflicting priorities between executives, line managers, and project managers

Although these quantitative and qualitative approaches still hold true to some degree, today we believe that the major component of planning failure is inappropriate or inadequate risk management, or having a project management methodology that does not provide any guidance for risk management.

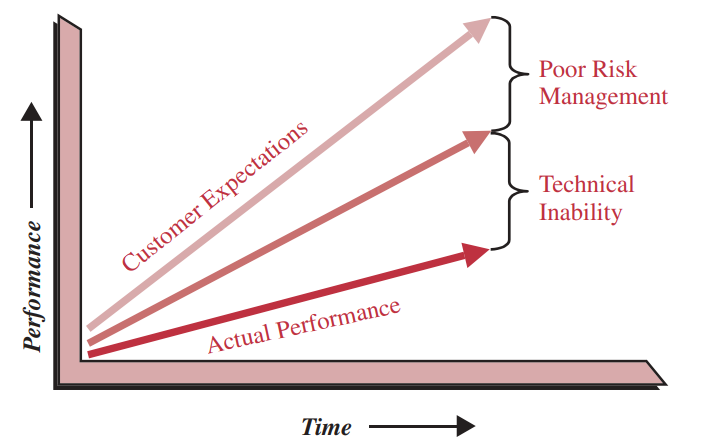

Sometimes, the risk management component of failure is not readily identified. For example, look at Figure 2–17. The actual performance delivered by the contractor was significantly less than the customer’s expectations. Is the difference due to poor technical ability or a combination of technical inability and poor risk management? Today we believe that it is a combination.

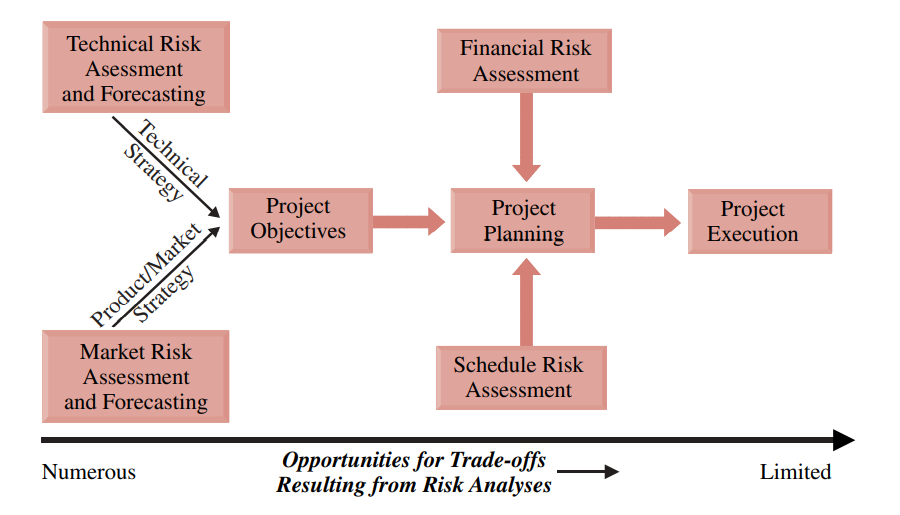

When a project is completed, companies perform a lessons-learned review. Sometimes lessons learned are inappropriately labeled and the true reason for the risk event is not known. Figure 2–18 illustrates the relationship between the marketing personnel and technical personnel when undertaking a project to develop a new product. If the project is completed with actual performance being less than customer expectations, is it because of poor risk management by the technical assessment and forecasting personnel or poor marketing risk assessment? The relationship between marketing and technical risk

management is not always clear.

Figure 2–18 also shows that opportunities for trade-offs diminish as we get further downstream on the project. There are numerous opportunities for trade-offs prior to establishing the final objectives for the project. In other words, if the project fails, it may be because of the timing when the risks were analyzed.

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.