Project management has matured as an outgrowth of the need to develop and produce complex and/or large projects in the shortest possible time, within anticipated cost, with required reliability and performance, and (when applicable) to realize a profit. Granted that organizations have become so complex that traditional organizational structures and relationships no longer allow for effective management, how can executives determine which organizational form is best, especially since some projects last for only a few weeks or months while others may take years?

To answer this question, we must first determine whether the necessary characteristics exist to warrant a project management organizational form. Generally speaking, the project management approach can be effectively applied to a onetime undertaking that is:

● Definable in terms of a specific goal

● Infrequent, unique, or unfamiliar to the present organization

● Complex with respect to interdependence of detailed tasks

● Critical to the company

Once a group of tasks is selected and considered to be a project, the next step is to define the kinds of projects, described in Section 2.5. These include individual, staff, special, and matrix or aggregate projects.

Unfortunately, many companies do not have a clear definition of what a project is. As a result, large project teams are often constructed for small projects when they could be handled more quickly and effectively by some other structural form. All structural forms have their advantages and disadvantages, but the project management approach appears to be the best possible alternative.

The basic factors that influence the selection of a project organizational form are:

● Project size

● Project length

● Experience with project management organization

● Philosophy and visibility of upper-level management

● Project location

● Available resources

● Unique aspects of the project

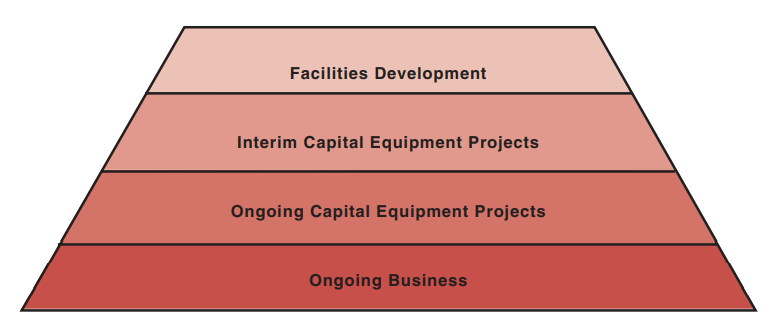

This last item requires further comment. Project management (especially with a matrix) usually works best for the control of human resources and thus may be more applicable to labor-intensive projects rather than capital-intensive projects. Labor-intensive organizations have formal project management, whereas capital-intensive organizations may use informal project management. Figure 3–13 shows how matrix management was implemented by an electric equipment manufacturer. The company decided to use fragmented matrix management for facility development projects. After observing the success of the fragmented matrix, the executives expanded matrix operations to include interim and ongoing capital equipment projects. The first three levels were easy to implement. The fourth level, ongoing business, was more difficult to convert to matrix because of functional management resistance and the fear of losing authority.

Four fundamental parameters must be analyzed when considering implementation of

a project organizational form:

● Integrating devices

● Authority structure

● Influence distribution

● Information system

Project management is a means of integrating all company efforts, especially research and development, by selecting an appropriate organizational form. Two questions arise when we think of designing the organization to facilitate the work of the integrators:

● Is it better to establish a formal integration department, or simply to set up integrating positions independent of one another?

● If individual integrating positions are set up, how should they be related to the larger structure?

Informal integration works best if, and only if, effective collaboration can be achieved between conflicting units. Without any clearly defined authority, the role of the integrator is simply to act as an exchange medium across the interface of two functional units. As the size of the organization increases, formal integration positions must exist, especially in situations where intense conflict can occur (e.g., research and development).

Not all organizations need a pure matrix structure to achieve this integration. Many problems can be solved simply through the chain of command, depending on the size of the organization and the nature of the project. The organization needed to achieve project control can vary in size from one person to several thousand people. The organizational structure needed for effective project control is governed by the desires of top management and project circumstances.

Unfortunately, integration and specialization appear to be diametrically opposed. As described by Davis:

When organization is considered synonymous with structure, the dual needs of specialization and coordination are seen as inversely related, as opposite ends of a single variable, as the horns of a dilemma. Most managers speak of this dilemma in terms of the centralization–decentralization variable. Formulated in this manner, greater specialization leads to more difficulty in coordinating the differentiated units. This is why the (de)centralization pendulum is always swinging, and no ideal point can be found at which it can come to rest.

The division of labor in a hierarchical pyramid means that specialization must be defined either by function, by product, or by area. Firms must select one of these dimensions as primary and then subdivide the other two into subordinate units further down the pyramid. The appropriate choice for primary, secondary and tertiary dimensions is based largely upon the strategic needs of the enterprise.

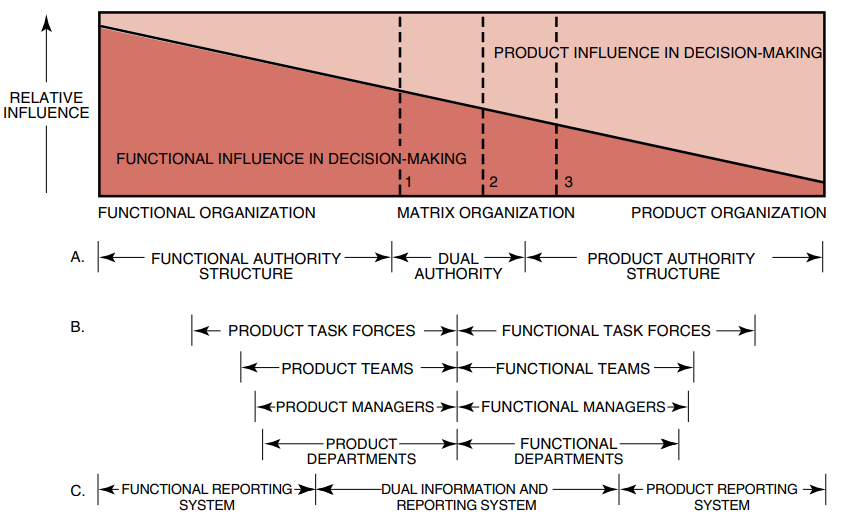

Top management must decide on the authority structure that will control the integration mechanism. The authority structure can range from pure functional authority (traditional management), to product authority (product management), and finally to dual authority (matrix management). This range is shown in Figure 3–14. From a management point of view, organizational forms are often selected based on how much authority top management wishes to delegate or surrender.

Reprinted with permission from Business Horizons, February 1971 (p. 37). Copyright © 1971 by the

Board of Trustees at Indiana University.

Integration of activities across functional boundaries can also be accomplished by influence. Influence includes such factors as participation in budget planning and approval, design changes, location and size of offices, salaries, and so on. Influence can also cut administrative red tape and develop a much more unified informal organization.

Matrix structures are characterized as strong or weak based on the relative influence that the project manager possesses over the assigned functional resources. When the project manager has more “relative influence” over the performance of the assigned resources than does the line manager, the matrix structure is a strong matrix. In this case, the project manager usually has the knowledge to provide technical direction, assign responsibilities, and may even have a strong input into the performance evaluation of the assigned personnel. If the balance of influence tilts in favor of the line manager, then the matrix is referred to as a weak matrix.

Information systems also play an important role. Previously we stated that one of the advantages of several project management structures is the ability to make both rapid and timely decisions with almost immediate response to environmental changes. Information systems are designed to get the right information to the right person at the right time in a cost-effective manner. Organizational functions must facilitate the flow of information through the management network.

Galbraith has described additional factors that can influence organizational selection.

These factors are:

● Diversity of product lines

● Rate of change of the product lines

● Interdependencies among subunits

● Level of technology

● Presence of economies of scale

● Organizational size

A diversity of project lines requires both top-level and functional managers to maintain knowledge in all areas. Diversity makes it more difficult for managers to make realistic estimates concerning resource allocations and the control of time, cost, schedules, and technology. The systems approach to management requires sufficient information and alternatives to be available so that effective trade-offs can be established. For diversity in a high-technology environment, the organizational choice might, in fact, be a trade-off between the flow of work and the flow of information. Diversity tends toward strong product authority and control.

Many functional organizations consider themselves companies within a company and pride themselves on their independence. This attitude poses a severe problem in trying to develop a synergistic atmosphere. Successful project management requires that functional units recognize the interdependence that must exist in order for technology to be shared and schedule dates to be met. Interdependency is also required in order to develop strong communication channels and coordination.

The use of new technologies poses a serious problem in that technical expertise must be

established in all specialties, including engineering, production, material control, and safety.

Maintaining technical expertise works best in strong functional disciplines, provided the information is not purchased outside the organization. The main problem, however, is how to communicate this expertise across functional lines. Independent R&D units can be established, as opposed to integrating R&D into each functional department’s routine efforts.

Organizational control requirements are much more difficult in high-technology industries with ongoing research and development than with pure production groups. Economies of scale and size can also affect organizational selection. The economies of scale are most often controlled by the amount of physical resources that a company has available. For example, a company with limited facilities and resources might find it impossible to compete with other companies on production or competitive bidding for larger dollar-volume products. Such a company must rely heavily on maintaining multiple projects (or products), each of low cost or volume, whereas a larger organization may need only three or four projects large enough to sustain the organization. The larger the economies of scale, the more the organization tends to favor pure functional management. The size of the organization is important in that it can limit the amount of technical expertise in the economies of scale. While size may have little effect on the organizational structure, it does have a severe impact on the economies of scale. Small companies, for example, cannot maintain large specialist staffs and, therefore, incur a larger cost for lost

specialization and lost economies of scale.

The four factors described above for organizational form selections together with the six alternatives of Galbraith can be regarded as universal. Beyond these universal factors, we must look at the company in terms of its product, business base, and personnel.

Goodman has defined a set of sub factors related to R&D groups:

● Clear location of responsibility

● Ease and accuracy of communication

● Effective cost control

● Ability to provide good technical supervision

● Flexibility of staffing

● Importance to the company

● Quick reaction capability to sudden changes in the project

● Complexity of the project

● Size of the project with relation to other work in-house

● Form desired by customer

● Ability to provide a clear path for individual promotion

Goodman asked general managers and project managers to select from the above list and rank the factors from most important to least important in designing an organization.

With one exception—flexibility of staffing—the response from both groups correlated to a coefficient of 0.811. Clear location of responsibility was seen as the most important factor, and a path for promotion the least important.

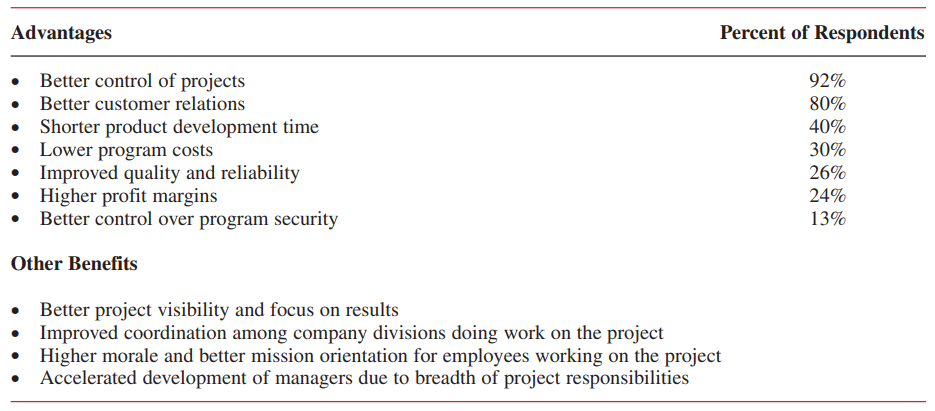

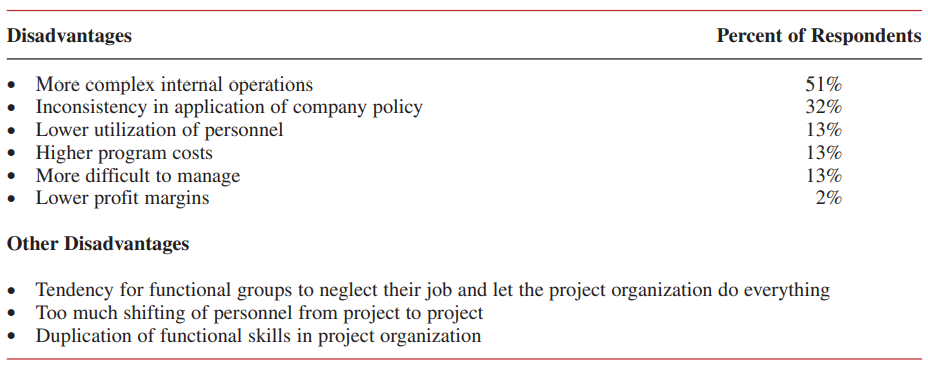

Middleton conducted a mail survey of aerospace firms in an attempt to determine how well the companies using project management met their objectives. Forty-seven responses were received. Tables 3–8 and 3–9 identify the results. Middleton stated, “In evaluating the results of the survey, it appears that a company taking the project organization approach can be reasonably certain that it will improve controls and customer (out-of-company) relations, but internal operations will be more complex.”

The way in which companies operate their project organization is bound to affect the organization, both during the operation of the project and after the project has been completed and personnel have been disbanded. The overall effects on the company must be looked at from a personnel and cost control standpoint. This will be accomplished, in depth, in later chapters.

Although project management is growing, the creation of a project organization does not necessarily ensure that an assigned objective will be accomplished successfully. Furthermore, weaknesses can develop in the areas of maintaining capability and structural changes.

Project management structures have been known to go out of control:

When a matrix appears to be going out of control, executives revert to classical management. This results in:

● Reduced authority for the project manager

● All project decision-making performed at executive levels

● Increase in executive meddling in projects

● Creation of endless manuals for job descriptions

Source: Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. An exhibit from “How to Set Up a Project Organization,” by C. J.

Middleton, March–April, 1967 (pp. 73–82). Copyright © 1967 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights

reserved

This can sometimes be prevented by frequently asking for authority/responsibility clarification and by the use of linear responsibility charts.

An almost predictable result of using the project management approach is the increase in management positions. Killian describes the results of two surveys:

One company compared its organization and management structure as it existed before it began forming project units with the structure that existed afterward. The number of departments had increased from 65 to 106, while total employment remained practically the same. The number of employees for every supervisor had dropped from 13.4 to 12.8. The company concluded that a major cause of this change was the project groups.

Another company uncovered proof of its conclusion when it counted the number of second-level and higher management positions. It found that it had 11 more vice presidents and directors, 35 more managers, and 56 more second-level supervisors. Although the company attributed part of this growth to an upgrading of titles, the effect of the project organization was the creation of 60 more management positions.

Source: Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. An exhibit from “How to Set Up a Project Organization,” by C. J.

Middleton, March–April, 1967 (pp. 73–82). Copyright © 1967 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights

reserved.

Although the project organization is a specialized, task-oriented entity, it seldom, if ever, exists apart from the traditional structure of the organization. All project management structures overlap the traditional structure. Furthermore, companies can have more than one project organizational form in existence at one time. A major steel product, for example, has a matrix structure for R&D and a product structure elsewhere.

Accepting a project management structure is a giant step from which there may be no return. The company may have to create more management positions without changing the total employment levels. In addition, incorporation of a project organization is almost always accompanied by the upgrading of jobs. In any event, management must realize that whichever project management structure is selected, a dynamic state of equilibrium will be necessary.

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.