PROJECT-DRIVEN VERSUS NON–PROJECT-DRIVEN ORGANIZATIONS

On the micro level, virtually all organizations are either marketing-, engineering-, or manufacturing- driven. But on the macro level, organizations are either project- or non–project-driven.

In a project-driven organization, such as construction or aerospace, all work is characterized through projects, with each project as a separate cost center having its own profit-and-loss statement. The total profit to the corporation is simply the summation of the profits on all projects. In a project-driven organization, everything centers around the projects.

In the non–project-driven organization, such as low-technology manufacturing, profit and loss are measured on vertical or functional lines. In this type of organization, projects exist merely to support the product lines or functional lines. Priority resources are assigned to the revenue-producing functional line activities rather than the projects.

Project management in a non–project-driven organization is generally more difficult for these reasons:

● Projects may be few and far between.

● Not all projects have the same project management requirements, and therefore

they cannot be managed identically. This difficulty results from poor understanding of project management and a reluctance of companies to invest in proper training.

● Executives do not have sufficient time to manage projects themselves, yet refuse to delegate authority.

● Projects tend to be delayed because approvals most often follow the vertical chain of command. As a result, project work stays too long in functional departments.

● Because project staffing is on a “local” basis, only a portion of the organization understands project management and sees the system in action.

● There is heavy dependence on subcontractors and outside agencies for project management expertise.

Non–project-driven organizations may also have a steady stream of projects, all of which are usually designed to enhance manufacturing operations. Some projects may be customer-requested, such as:

● The introduction of statistical dimensioning concepts to improve process control

● The introduction of process changes to enhance the final product

● The introduction of process change concepts to enhance product reliability

If these changes are not identified as specific projects, the result can be:

● Poorly defined responsibility areas within the organization

● Poor communications, both internal and external to the organization

● Slow implementation

● A lack of a cost-tracking system for implementation

● Poorly defined performance criteria

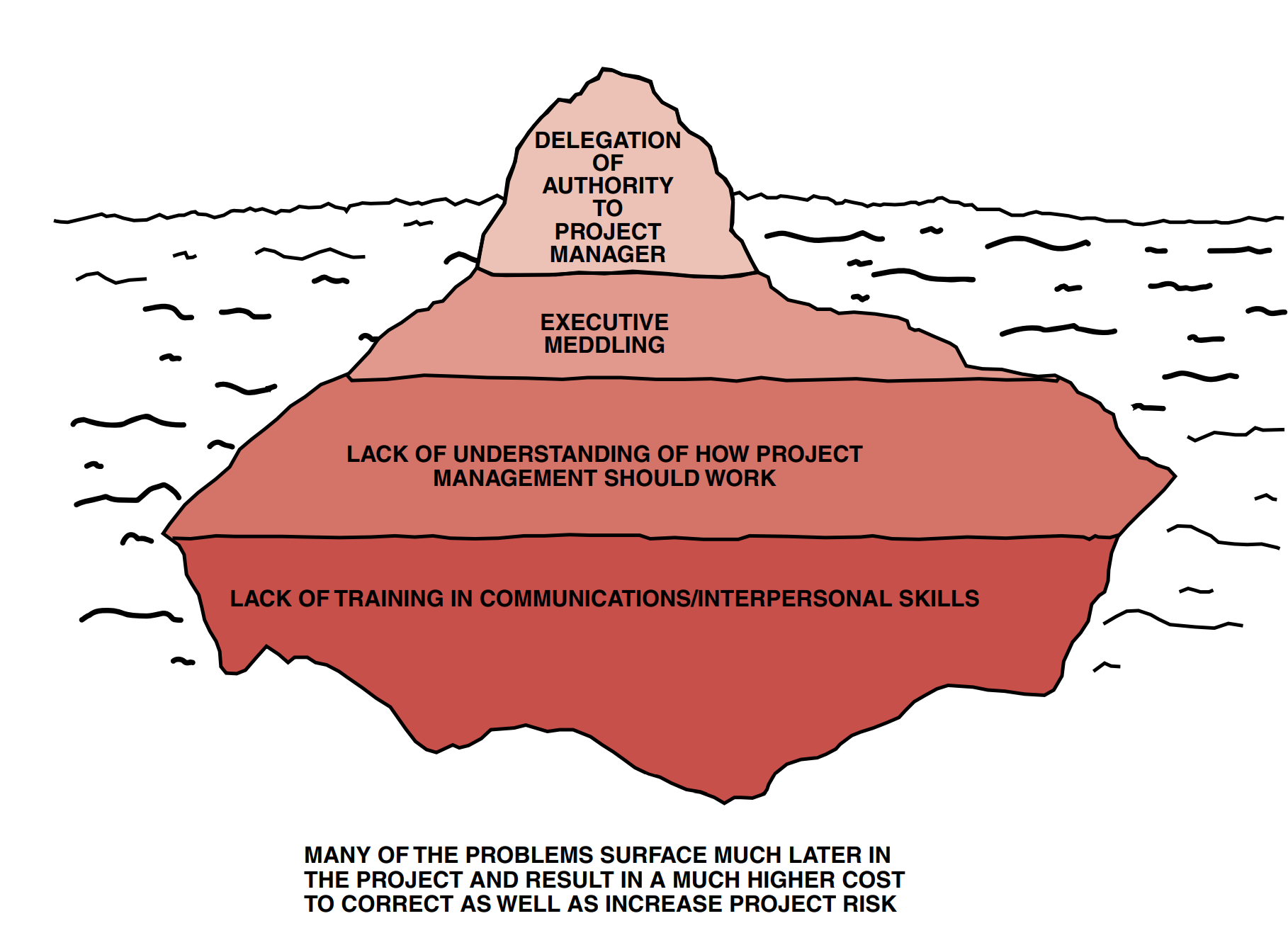

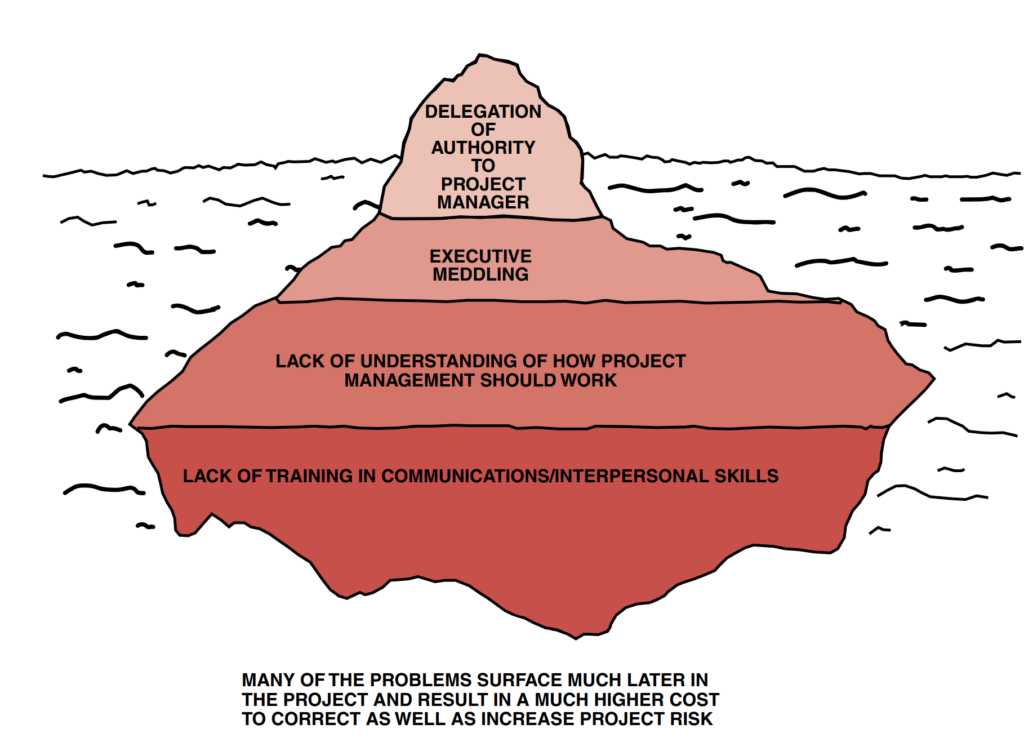

Figure 1–5 shows the tip-of-the-iceberg syndrome, which can occur in all types of organizations but is most common in non–project-driven organizations. On the surface, all we see is a lack of authority for the project manager. But beneath the surface we see the causes; there is excessive meddling due to lack of understanding of project management, which, in turn, resulted from an inability to recognize the need for proper training.

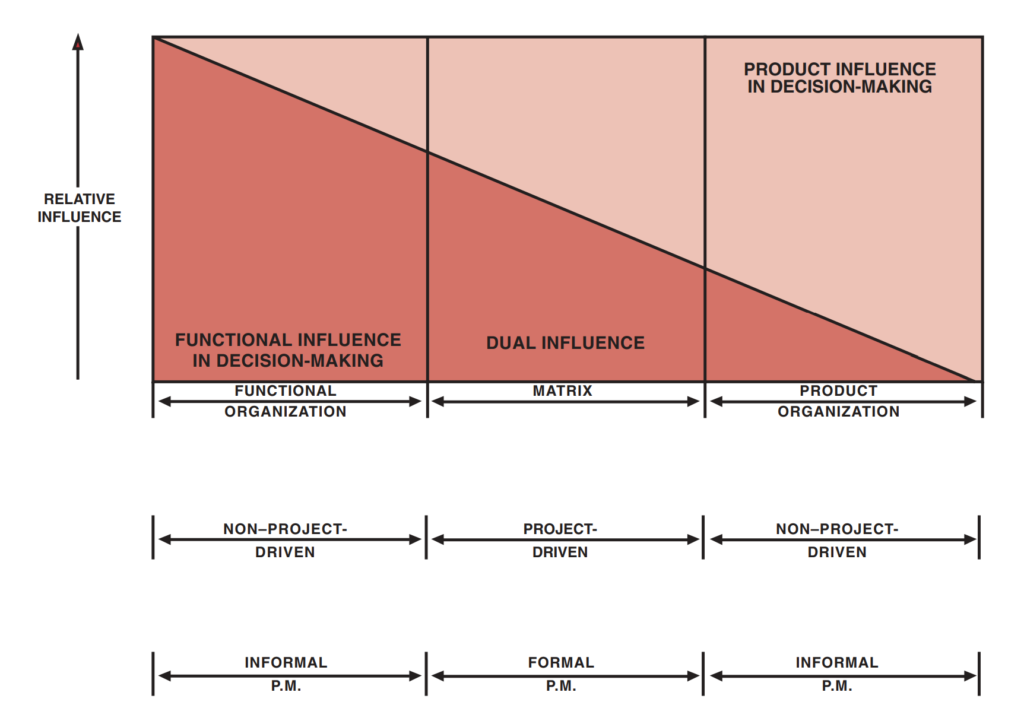

In the previous sections we stated that project management could be handled on either

a formal or an informal basis. As can be seen from Figure 1–6, informal project management most often appears in on–project-driven organizations. It is doubtful that informal project management would work in a project-driven organization where the project manager has profit-and-loss responsibility.

CLASSIFICATION OF PROJECTS

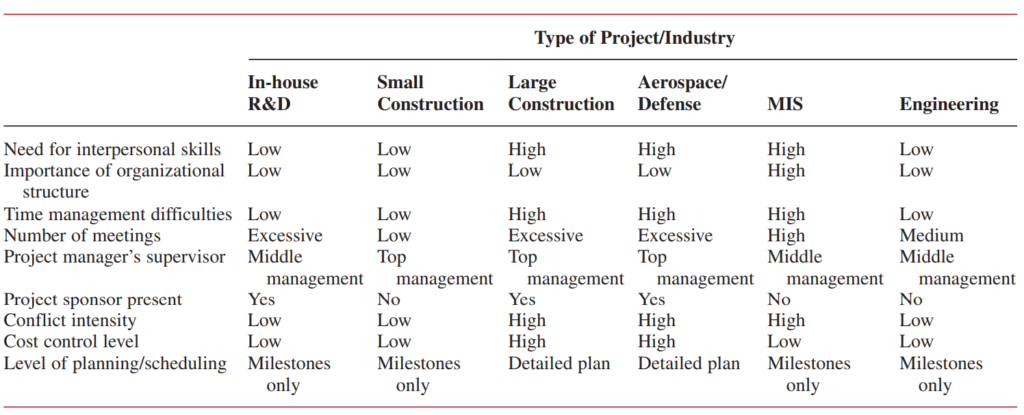

The principles of project management can be applied to any type of project and to any industry. However, the relative degree of importance of these principles can vary from project to project and industry to industry. Table 1–4 shows a brief comparison of certain industries/projects.

For those industries that are project-driven, such as aerospace and large construction, the high dollar value of the projects mandates a much more rigorous project management approach. For non–project-driven industries, projects may be managed more informally than formally, especially if no immediate profit is involved.

LOCATION OF THE PROJECT MANAGER

The success of project management could easily depend on the location of the project manager within the organization. Two questions must be answered:

● What salary should the project manager earn?

● To whom should the project manager report?

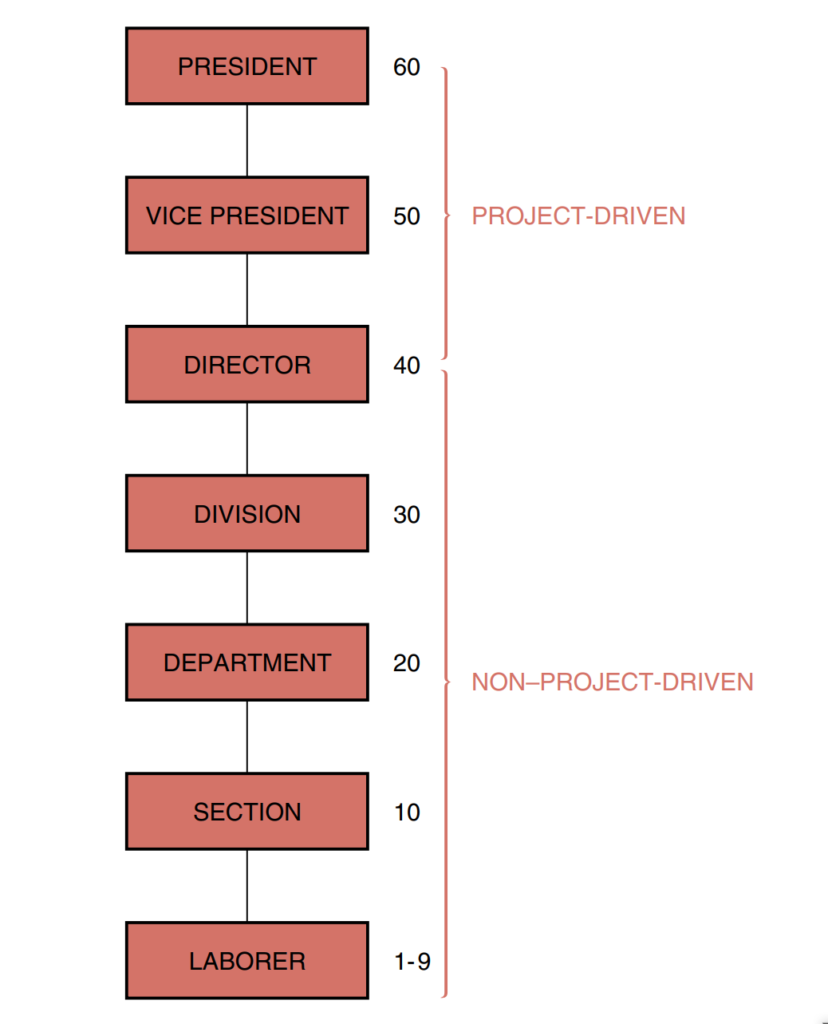

Figure 1–8 shows a typical organizational hierarchy (the numbers represent pay grades). Ideally, the project manager should be at the same pay grade as the individuals with whom he must negotiate on a daily basis. Using this criterion, and assuming that the project manager interfaces at the department manager level, the project manager should

earn a salary between grades 20 and 25. A project manager earning substantially more or less money than the line manager will usually create conflict. The ultimate reporting location of the project manager (and perhaps his salary) is heavily dependent on whether the organization is project- or non–project-driven, and whether the project manager is responsible for profit or loss.

Project managers can end up reporting both high and low in an organization during the life cycle of the project. During the planning phase of the project, the project manager may report high, whereas during implementation, he may report low. Likewise, the positioning of the project manager may be dependent on the risk of the project, the size of the project, or the customer.

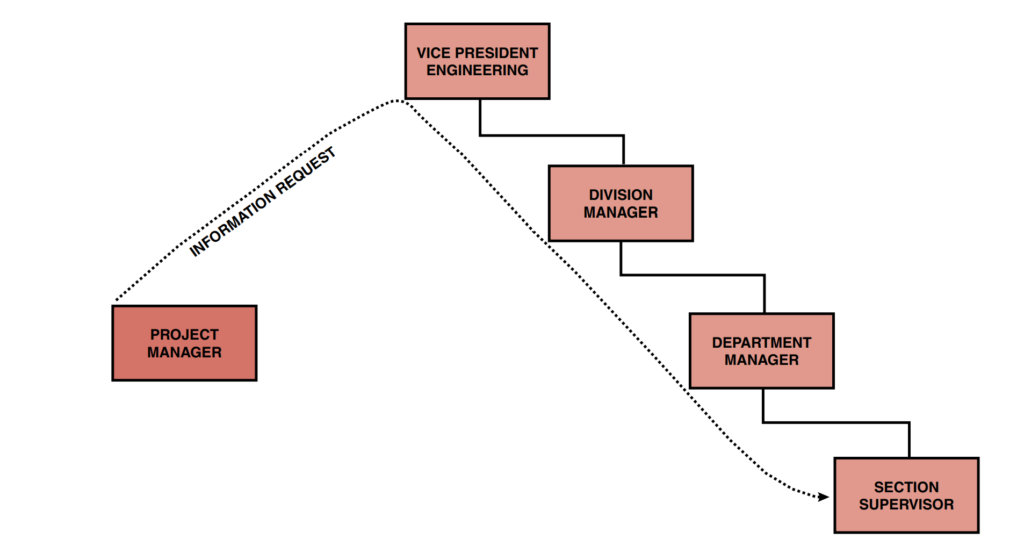

Finally, it should be noted that even if the project manager reports low, he should still have the right to interface with top executives during project planning although there may be two or more reporting levels between the project manager and executives. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the project manager should have the right to go directly into the depths of the organization instead of having to follow the chain of command downward, especially during

planning. As an example, see Figure 1–9. The project manager had two weeks to plan and price out a small project. Most of the work was to be accomplished within one section. The project manager was told that all requests for work, even estimating, had to follow the chain of command from the executive down through the section supervisor. By the time the request was received by the section supervisor, twelve of the fourteen days were gone, and only an

order-of-magnitude estimate was possible. The lesson to be learned here is:

“The chain of command should be used for approving projects, not planning them.”

Forcing the project manager to use the chain of command (in either direction) for project

planning can result in a great deal of unproductive time and idle time cost.

DIFFERING VIEWS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Many companies, especially those with project-driven organizations, have differing views of project management. Some people view project management as an excellent means to achieving objectives, while others view it as a threat. In project-driven organizations, there are three career paths that lead to executive management:

● Through project management

● Through project engineering

● Through line management

In project-driven organizations, the fast-track position is in project management, whereas in a non–project-driven organization, it would be line management. Even though line managers support the project management approach, they resent the project manager because of his promotions and top-level visibility. In one construction company, a department manager was told that he had no chance for promotion above his present department manager position unless he went into project management or project engineering where he could get to know the operation of the whole company. A second construction company requires that individuals aspiring to become a department manager first spend a “tour of duty” as an assistant project manager or project engineer.

Executives may dislike project managers because more authority and control must be delegated. However, once executives realize that it is a sound business practice, it becomes important, as shown in the following letter5:

In order to sense and react quickly and to insure rapid decision-making, lines of communication should be the shortest possible between all levels of the organization. People with the most knowledge must be available at the source of the problem, and they must have decision-making authority and responsibility. Meaningful data must be available on a

timely basis and the organization must be structured to produce this environment.

In the aerospace industry, it is a serious weakness to be tied to fixed organization charts, plans, and procedures. With regard to organization, we successfully married the project concept of management with a central function concept. What we came up with is an organization within an organization—one to ramrod the day-to-day problems; the other to provide support for existing projects and to anticipate the requirements for future projects.

The project system is essential in getting complicated jobs done well and on time, but it solves only part of the management problem. When you have your nose to the project grindstone, you are often not in a position to see much beyond that project. This is where the central functional organization comes in. My experience has been that you need this central organization to give you depth, flexibility, and perspective. Together, the two parts

permit you to see both the woods and the trees.

Initiative is essential at all levels of the organization. We try to press the level of decision to the lowest possible rung of the managerial ladder. This type of decision-making

provides motivation and permits recognition for the individual and the group at all levels.

It stimulates action and breeds dedication.

With this kind of encouragement, the organization can become a live thing—sensitive to problems and able to move in on them with much more speed and understanding than would be normally expected in a large operation. In this way, we can regroup or reorganize easily as situations dictate and can quickly focus on a “crisis.” In this industry a company must always be able to reorient itself to meet new objectives. In a more staid, old-line organization, frequent reorientation usually accompanied by a corresponding shift of people’s activities, could be most upsetting. However, in the aerospace industry, we must be prepared for change. The entire picture is one of change.

CONCURRENT ENGINEERING: A PROJECT MANAGEMENT APPROACH

In the past decade, organizations have become more aware of the fact that America’s most formidable weapon is its manufacturing ability, and yet more and more work seems to be departing for Southeast Asia and the Far East. If America and other countries are to remain competitive, then survival may depend on the manufacturing of a quality product and a rapid introduction into the marketplace. Today, companies are under tremendous pressure

to rapidly introduce new products because product life cycles are becoming shorter. As a result, organizations no longer have the luxury of performing work in series.

Concurrent or simultaneous engineering is an attempt to accomplish work in parallel rather than in series. This requires that marketing, R&D, engineering, and production are all actively involved in the early project phases and making plans even before the product design has been finalized. This concept of current engineering will accelerate product development, but it does come with serious and potentially costly risks, the largest one being the cost of rework.

Almost everyone agrees that the best way to reduce or minimize risks is for the organization to plan better. Since project management is one of the best methodologies to foster better planning, it is little wonder that more organizations are accepting project management as a way of life.

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.