DEFINING PROJECT SUCCESS

In the previous section, we defined project success as the completion of an activity within the constraints of time, cost, and performance. This was the definition used for the past twenty years or so. Today, the definition of project success has been modified to include completion:

● Within the allocated time period

● Within the budgeted cost

● At the proper performance or specification level

● With acceptance by the customer/user

● With minimum or mutually agreed upon scope changes

● Without disturbing the main work flow of the organization

● Without changing the corporate culture

The last three elements require further explanation. Very few projects are completed within the original scope of the project. Scope changes are inevitable and have the potential to destroy not only the morale on a project, but the entire project. Scope changes must be held to a minimum and those that are required must be approved by both the project manager and the customer/user.

Project managers must be willing to manage (and make concessions/trade-offs, if necessary) such that the company’s main work flow is not altered. Most project managers view themselves as self-employed entrepreneurs after project go-ahead, and would like to divorce their project from the operations of the parent organization.

This is not always possible. The project manager must be willing to manage within the guidelines, policies, procedures, rules, and directives of the parent organization.

All corporations have corporate cultures, and even though each project may be inherently different, the project manager should not expect his assigned personnel to deviate from cultural norms. If the company has a cultural standard of openness and honesty when dealing with customers, then this cultural value should remain in place for all projects, regardless of who the customer/user is or how strong the project manager’s desire for success is.

As a final note, it should be understood that simply because a project is a success does not mean that the company as a whole is successful in its project management endeavors.

Excellence in project management is defined as a continuous stream of successfully managed projects. Any project can be driven to success through formal authority and strong executive meddling. But in order for a continuous stream of successful projects to occur, there must exist a strong corporate commitment to project management, and this commitment must be visible.

THE PROJECT MANAGER–LINE MANAGER INTERFACE

We have stated that the project manager must control company resources within time, cost,

and performance. Most companies have six resources:

● Money

● Manpower

● Equipment

● Facilities

● Materials

● Information/technology

Actually, the project manager does not control any of these resources directly, except perhaps money (i.e., the project budget).1 Resources are controlled by the line managers, functional managers, or, as they are often called, resources managers. Project managers must, therefore, negotiate with line managers for all project resources. When we say that

project managers control project resources, we really mean that they control those resources (which are temporarily loaned to them) through line managers.

It should become obvious at this point that successful project management is strongly dependent on:

● A good daily working relationship between the project manager and those line

managers who directly assign resources to projects

● The ability of functional employees to report vertically to line managers at the

same time that they report horizontally to one or more project managers

These two items become critical. In the first item, functional employees who are assigned to a project manager still take technical direction from their line managers. Second, employees who report to multiple managers will always favor the manager who controls their purse strings. Thus, most project managers appear always to be at the mercy of the line managers.

Classical management has often been defined as a process in which the manager does not necessarily perform things for himself, but accomplishes objectives through others in a group situation. This basic definition also applies to the project manager. In addition, a project manager must help himself. There is nobody else to help him.

If we take a close look at project management, we will see that the project manager actually works for the line managers, not vice versa. Many executives do not realize this. They have a tendency to put a halo around the head of the project manager and give him a bonus at project termination, when, in fact, the credit should go to the line managers, who are continually pressured to make better use of their resources. The project manager is simply the

agent through whom this is accomplished. So why do some companies glorify the project management position?

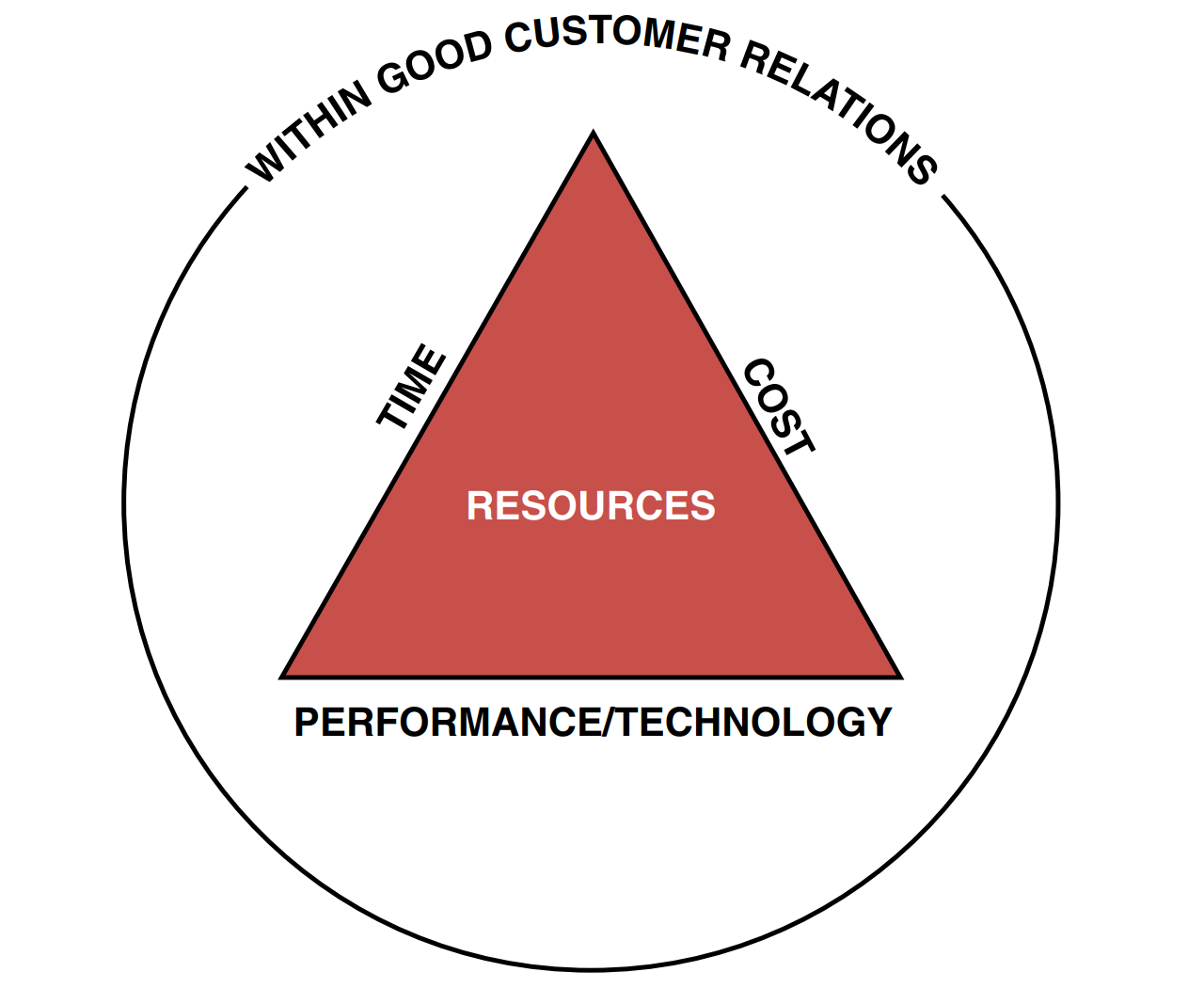

To illustrate the role of the project manager, consider the time, cost, and performance constraints shown in Figure 1–2. Many functional managers, if left alone, would recognize only the performance constraint: “Just give me another $50,000 and two more months, and I’ll give you the ideal technology.”

The project manager, as part of these communicating, coordinating, and integrating responsibilities, reminds the line managers that there are also time and cost constraints on the project. This is the starting point for better resource control.

Project managers depend on line managers. When the project manager gets in trouble, the only place he can go is to the line manager because additional resources are almost always required to alleviate the problems. When a line manager gets in trouble, he usually goes first to the project manager and requests either additional funding or some type of authorization for scope changes.

To illustrate this working relationship between the project and line managers, consider

the following situation:

Project Manager (addressing the line manager): “I have a serious problem. I’m looking at a $150,000 cost overrun on my project and I need your help. I’d like you to do the same amount of work that you are currently scheduled for but in 3,000 fewer man-hours. Since your organization is burdened at $60/hour, this would more than compensate for the cost overrun.”

Line Manager: “Even if I could, why should I? You know that good line managers can always make work expand to meet budget. I’ll look over my manpower curves and let you know tomorrow.”

The following day . . .

Line Manager: “I’ve looked over my manpower curves and I have enough work to keep my people employed. I’ll give you back the 3,000 hours you need, but remember, you owe me one!”

Several months later . . .

Line Manager: “I’ve just seen the planning for your new project that’s supposed to start two months from now. You’ll need two people from my department. There are two employees that I’d like to use on your project. Unfortunately, these two people are available now. If I don’t pick these people up on your charge number right now, some other project might pick them up in the interim period, and they won’t be available when your project starts.”

Project Manager: “What you’re saying is that you want me to let you sandbag against one of my charge numbers, knowing that I really don’t need them.”

Line Manager: “That’s right. I’ll try to find other jobs (and charge numbers) for them to work on temporarily so that your project won’t be completely burdened. Remember, you owe me one.”

Project Manager: “O.K. I know that I owe you one, so I’ll do this for you. Does this make us even?”

Line Manager: “Not at all! But you’re going in the right direction.”

When the project management–line management relationship begins to deteriorate, the project almost always suffers. Executives must promote a good working relationship between line and project management. One of the most common ways of destroying this relationship is by asking, “Who contributes to profits—the line or project manager?”

Project managers feel that they control all project profits because they control the budget.

The line managers, on the other hand, argue that they must staff with appropriately budgeted-for personnel, supply the resources at the desired time, and supervise performance. Actually, both the vertical and horizontal lines contribute to profits. These types of conflicts can destroy the entire project management system.

The previous examples should indicate that project management is more behavioral

than quantitative. Effective project management requires an understanding of:

● Quantitative tools and techniques

● Organizational structures

● Organizational behavior

Most people understand the quantitative tools for planning, scheduling, and controlling work. It is imperative that project managers understand totally the operations of each line organization. In addition, project managers must understand their own job description, especially where their authority begins and ends. During an in-house seminar on engineering project management, the author asked one of the project engineers to provide a description of his job as a project engineer. During the discussion that followed, several project managers and line managers said that there was a great deal of overlap between their job descriptions and that of the project engineer.

Organizational behavior is important because the functional employees at the interface position find themselves reporting to more than one boss—a line manager and one project manager for each project they are assigned to. Executives must provide proper training so functional employees can report effectively to multiple managers.

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.