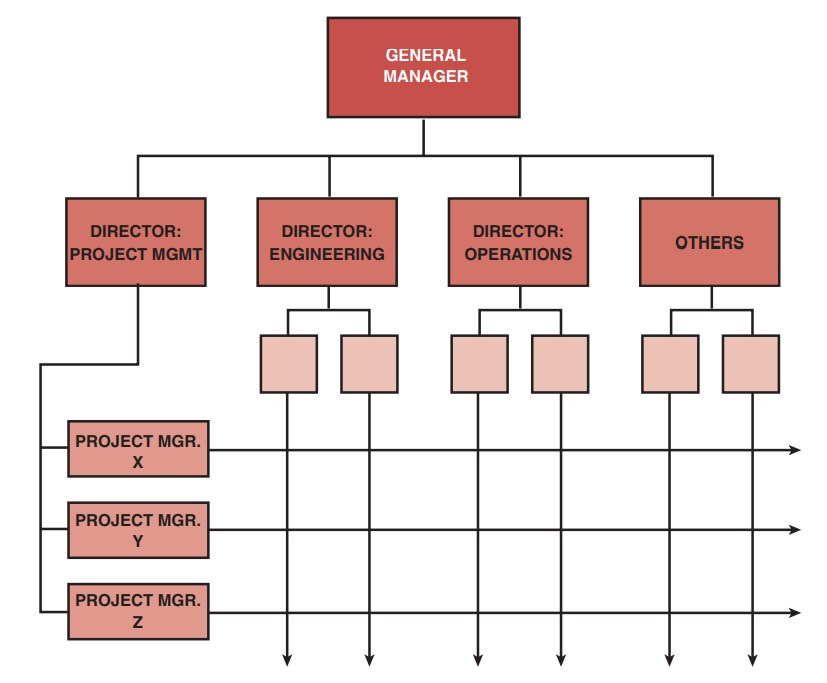

The matrix can take many forms, but there are basically three common varieties. Each type represents a different degree of authority attributed to the program manager and indirectly identifies the relative size of the matrix structures company. As an example, in the matrix of Figure 3–6, all program managers report directly to the general manager. This type of arrangement works best for small companies that have few projects and assumes that the general manager has sufficient time to coordinate activities between his project managers. In this type of arrangement, all conflicts between projects are referred to the general manager for resolution. As companies grow in size and the number of projects, the general manager will find it increasingly difficult to act as the focal point for all projects. A new position must be created, that of director of programs, or manager of programs or projects, who is responsible for all program management. See Figure 3–7.

Beck has elaborated on the basic role of this new position, the manager of project

managers (M.P.M.):

One difference in the roles of the M.P.M. and the project manager is that the M.P.M. must place a great deal more emphasis on the overview of a project than on the nuts and bolts, tools, networks and the details of managing the project. The M.P.M. must see how the project fits into the overall organizational plan and how projects interrelate. His perspective is a little different from the project manager who is looking at the project on its own merits rather than how it fits into the overall organization.

The M.P.M. is a project manager, a people manager, a change manager and a systems manager. In general, one role cannot be considered more important than the other. The M.P.M. has responsibilities for managing the projects, directing and leading people and the project management effort, and planning for change in the organization. The Manager of Project Managers is a liaison between the Project Management Department and upper management as well as functional department management and acts as a systems manager when serving as a liaison.

Executives contend that an effective span of control is five to seven people. Does this apply to the director of project management as well? Consider a company that has fifteen projects going on at once. There are three projects over $5 million, seven are between $1 and $3 million, and five projects are under $700,000. Each project has a full-time project manager. Can all fifteen project managers report to the same person? The company solved this problem by creating a deputy director of project management. All projects over $1 million reported to the director, and all projects under $1 million went to the deputy director. The director’s rationale soon fell by the wayside when he found that the more severe problems that were occupying his time were occurring on projects with a smaller dollar volume, where flexibility in time, cost, and performance was nonexistent and trade-offs were almost impossible. If the project manager is actually a general manager, then the director of project management should be able to supervise effectively more than seven project managers. The desired span of control, of course, will vary from company to company and must take into account:

● The demands imposed on the organization by task complexity

● Available technology

● The external environment

● The needs of the organizational membership

● The types of customers and/or products

As companies expand, it is inevitable that new and more complex conflicts arise. The control of the engineering functions poses such a problem:

Should the project manager have ultimate responsibility for the engineering functions of a project, or should there be a deputy project manager who reports to the director of engineering and controls all technical activity?

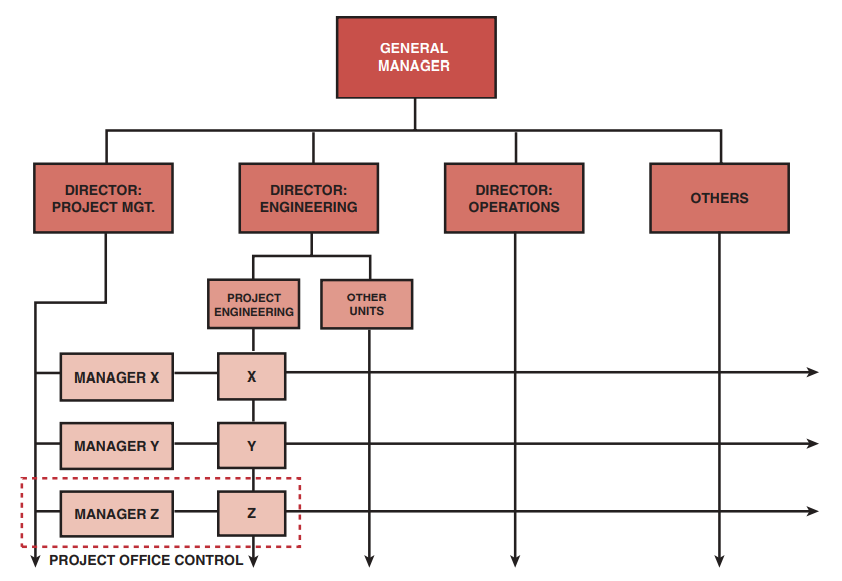

Although there are pros and cons for both arrangements, the problem resolved itself in the company mentioned above when projects grew so large that the project manager became unable to handle both the project management and project engineering functions. Then, as shown in Figure 3–8, a chief project engineer was assigned to each project as deputy project manager, but remained functionally assigned to the director of engineering. The project manager was now responsible for time and cost considerations, whereas the project engineer was concerned with technical performance. The project engineer can be either “solid” vertically and “dotted” horizontally, or vice versa. There are also situations where the project engineer may be “solid” in both directions. The decision usually rests with the director of engineering.

Of course, in a project where the project engineer would be needed on a part-time basis only,

he would be solid vertically and dotted horizontally.

Engineering directors usually demand that the project engineer be solid vertically in order to give technical direction. As one director of engineering stated, “Only engineers that report to me will have the authority to give technical direction to other engineers. After all, how else can I be responsible for the technical integrity of the product when direction comes from outside my organization?”

This subdivision of functions is necessary in order to control large projects adequately.

However, for small projects, say $100,000 or less, it is quite common on R&D projects for

an engineer to serve as the project manager as well as the project engineer. Here, the project manager must have technical expertise, not merely understanding. Furthermore, this individual can still be attached to a functional engineering support unit other than project engineering. As an example, a mechanical engineering department receives a government contract for $75,000 to perform tests on a new material. The proposal is written by an engineer attached to the department. When the contract is awarded, this individual, although not in the project engineering department, can fulfill the role of project manager and project engineer while still reporting to the manager of the mechanical engineering department. This arrangement works best (and is cost-effective) for short-duration projects that cross a minimum number of functional units.

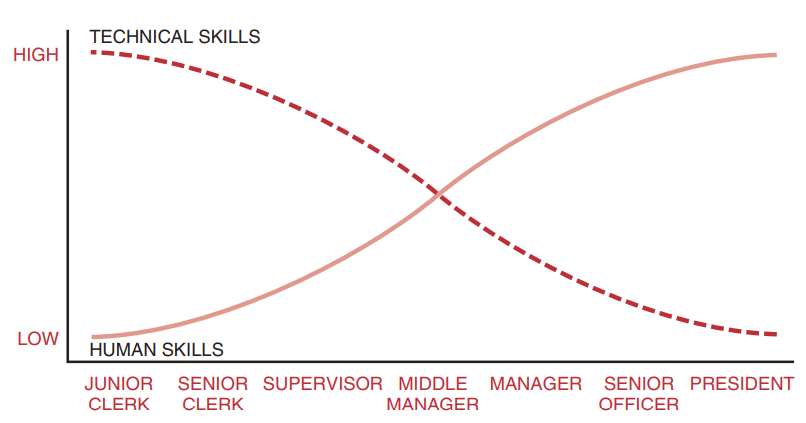

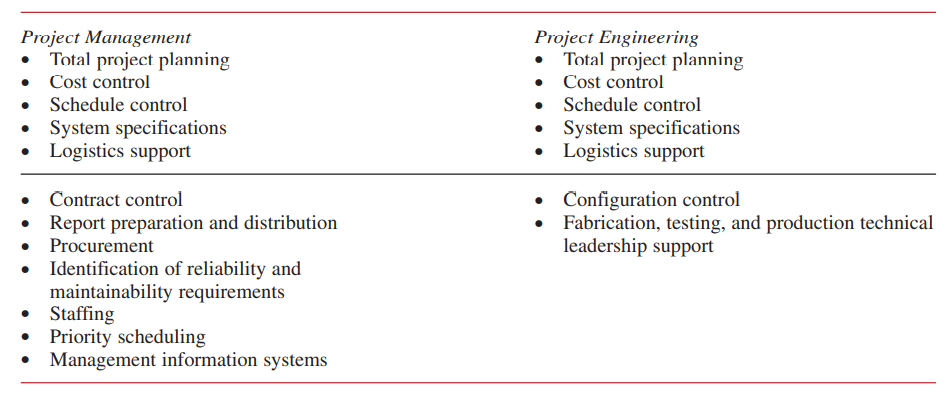

Finally, we must discuss the characteristics of a project engineer. In Figure 3–9, most people would place the project manager to the right of center with stronger human skills than technical skills, and the project engineer to the left of center with stronger technical skills than human skills. How far from the center point will the project manager and project engineer be? Today, many companies are merging project management and project engineering into one position. This can be seen in Table 3–7. The project manager and project engineer have similar functions above the line but different ones below the line. The main reason for separating project management from project engineering is so that the project engineer will remain “solid” to the director of engineering in order to have the full authority to give technical direction to engineering.

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.