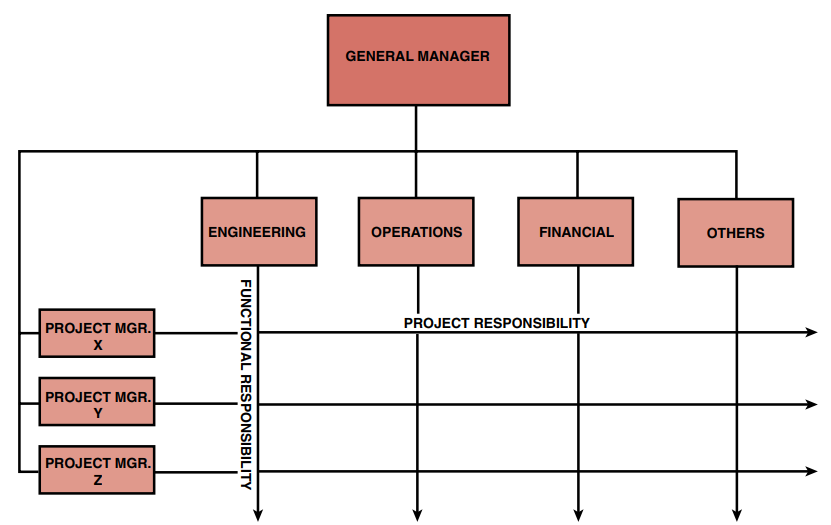

The matrix organizational form is an attempt to combine the advantages of the pure functional structure and the product organizational structure. This form is ideally suited for companies, such as construction, that are “project-driven.” Figure 3–6 shows a typical matrix structure. Each project manager reports directly to the vice president and general manager. Since each project represents a potential profit center, the power and authority used by the project manager come directly from the general manager. The project manager has total responsibility and accountability for project success. The functional departments, on the other hand, have functional responsibility to maintain technical excellence on the

project. Each functional unit is headed by a department manager whose prime responsibility is to ensure that a unified technical base is maintained and that all available information can be exchanged for each project. Department managers must also keep their people aware of the latest technical accomplishments in the industry.

Project management is a “coordinative” function, whereas matrix management is a collaborative function division of project management. In the coordinative or project organization, work is generally assigned to specific people or units who “do their own thing.” In the collaborative or matrix organization, information sharing may be mandatory, and several people maybe required for the same piece of work. In a project organization, authority for decision making and direction rests with the project leader, whereas in a matrix it rests with the team.

Certain ground rules exist for matrix development:

● Participants must spend full time on the project; this ensures a degree of loyalty.

● Horizontal as well as vertical channels must exist for making commitments.

● There must be quick and effective methods for conflict resolution.

● There must be good communication channels and free access between managers.

● All managers must have input into the planning process.

● Both horizontally and vertically oriented managers must be willing to negotiate for resources.

● The horizontal line must be permitted to operate as a separate entity except for administrative purposes.

Before describing the advantages and disadvantages of this structure, the organization

concepts must be introduced. The basis for the matrix approach is an attempt to create synergism through shared responsibility between project and functional management. Yet this is easier said than done. No two working environments are the same, and, therefore, no two companies will have the same matrix design. The following questions must be answered before a matrix structure can be successful:

● If each functional unit is responsible for one aspect of a project, and other parts are conducted elsewhere (possibly subcontracted to other companies), how can a synergistic environment be created?

● Who decides which element of a project is most important?

● How can a functional unit (operating in a vertical structure) answer questions and achieve project goals and objectives that are compatible with other projects?

The answers to these questions depend on mutual understanding between the project and functional managers. Since both individuals maintain some degree of authority, responsibility, and accountability on each project, they must continuously negotiate.

Unfortunately, the program manager might only consider what is best for his project (disregarding all others), whereas the functional manager might consider his organization more important than each project.

In order to get the job done, project managers need organizational status and authority. A corporate executive contends that the organization chart shown in Figure 3–6 can be modified to show that the project managers have adequate organizational authority by placing the department manager boxes at the tip of the functional responsibility arrowheads. With this approach, the project managers appear to be higher in the organization than their departmental counterparts but are actually equal in status. Executives who prefer this method must exercise caution because the line and project managers may not feel that there is still a balance of power.

Problem-solving in this environment is fragmented and diffused. The project manager acts as a unifying agent for project control of resources and technology. He must maintain open channels of communication to prevent sub optimization of individual projects.

In many situations, functional managers have the power to make a project manager look good, if they can be motivated to think about what is best for the project.

Unfortunately, this is not always accomplished. As stated by Mantell:

There exists an inevitable tendency for hierarchically arrayed units to seek solutions and to identify problems in terms of scope of duties of particular units rather than looking beyond them. This phenomenon exists without regard for the competence of the executive concerned. It comes about because of authority delegation and functionalism.

The project environment and functional environment cannot be separated; they must interact. The location of the project and functional unit interface is the focal point for all activities.

The functional manager controls departmental resources (i.e., people). This poses a problem because, although the project manager maintains the maximum control (through the line managers) over all resources including cost and personnel, the functional manager must provide staff for the project’s requirements. It is therefore inevitable that conflicts occur between functional and project managers:

These conflicts revolve about items such as project priority, manpower costs, and the assignment of functional personnel to the project manager. Each project manager will, of course, want the best functional operators assigned to his program. In addition to these problems, the accountability for profit and loss is much more difficult in a matrix organization than in a project organization. Project managers have a tendency to blame overruns on functional managers, stating that the cost of the function was excessive. Whereas functional managers have a tendency to blame excessive costs on project managers with the argument that there were too many changes, more work required than defined initially and other such arguments.

The individual placed at the interface position has two bosses: He must take direction from both the project manager and the functional manager. The merit review and hiring and firing responsibilities still rest with the department manager. Merit reviews are normally made by the functional manager after discussions with the program manager. The functional manager may not have the time to measure the progress of this individual continuously. He must rely on the word of the program manager for merit review and promotion. The interface members generally give loyalty to the person signing their merit review.

This poses a problem, especially if conflicting orders are given by the functional and project managers. The simplest solution is for the individual at the interface to ask the functional and project managers to communicate with each other to resolve the problem.

This type of situation poses a problem for project managers:

● How does a project manager motivate an individual working on a project (either part-time or full-time) so that his loyalties are with the project?

● How does a project manager convince an individual to perform work according to project direction and specifications when these requests may be in conflict with department policy, especially if the individual feels that his functional boss may not regard him favorably?

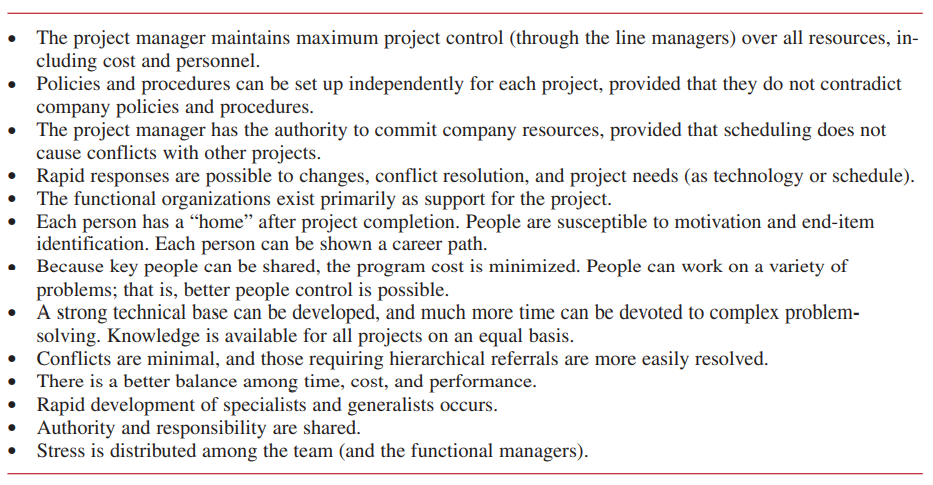

There are many advantages to matrix structures, as shown in Table 3–5. Functional units exist primarily to support a project. Because of this, key people can be shared and costs can be minimized. People can be assigned to a variety of challenging problems. Each person, therefore, has a “home” after project completion and a career path. People in these organizations are especially responsive to motivation and end-item identification. Functional managers find it easy to develop and maintain a strong technical base and can, therefore, spend more time on complex problem-solving. Knowledge can be shared for all

projects.

The matrix structure can provide a rapid response to changes, conflicts, and other project needs. Conflicts are normally minimal, but those requiring resolution are easily resolved using hierarchical referral.

This rapid response is a result of the project manager’s authority to commit company resources, provided that scheduling conflicts with other projects can be eliminated.

Furthermore, the project manager has the authority independently to establish his own project policies and procedures, provided that they do not conflict with company policies. This can do away with red tape and permit a better balance among time, cost, and performance.

The matrix structure provides us with the best of two worlds: the traditional structure and the matrix structure. The advantages of the matrix structure eliminate almost all of the disadvantages of the traditional structure. The word “matrix” often brings fear to the hearts of executives because it implies radical change, or at least they think that it does. If we take a close look at Figure 3–6, we can see that the traditional structure is still there. The matrix is simply horizontal lines superimposed over the traditional structure. The horizontal lines will come and go as projects start up and terminate, but the traditional structure will remain.

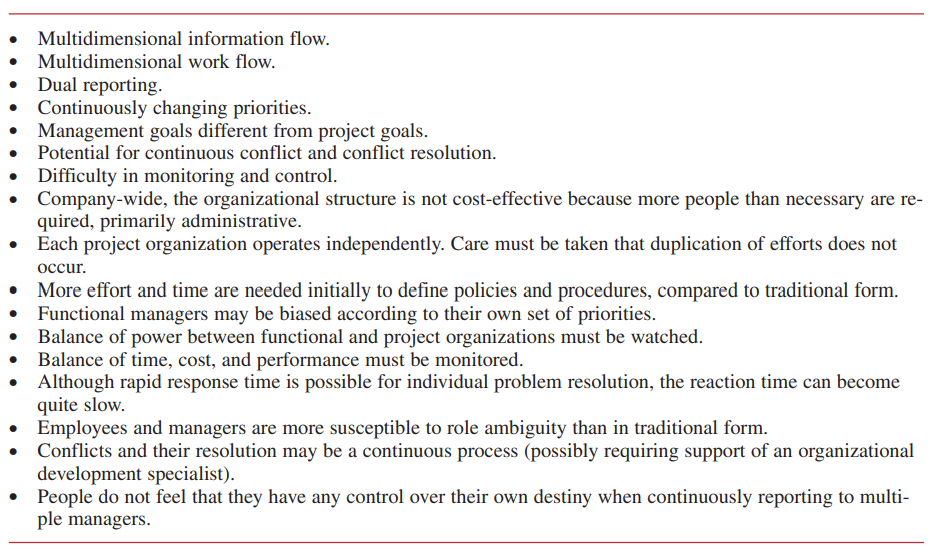

Matrix structures are not without their disadvantages, as shown in Table 3–6. The first

three elements are due to the horizontal and vertical work flow requirements of a matrix.

Actually the flow may even be multidimensional if the project manager has to report to customers or corporate or other personnel in addition to his superior and the functional line managers.

Most companies believe that if they have enough resources to staff all of the projects that come along, then the company is “overstaffed.” As a result of this philosophy, priorities may change continuously, perhaps even daily. Management’s goals for a project may be drastically different from the project’s goals, especially if executive involvement is lacking during the definition of a project’s requirements in the planning phase. In a matrix, conflicts and their resolution may be a continuous process, especially if priorities change continuously. Regardless of how mature an organization becomes, there will always exist

difficulty in monitoring and control because of the complex, multidirectional work flow.

Another disadvantage of the matrix organization is that more administrative personnel are needed to develop policies and procedures, and therefore both direct and indirect administrative costs will increase. In addition, it is impossible to manage projects with a matrix if there are steep horizontal or vertical pyramids for supervision and reporting, because each manager in the pyramid will want to reduce the authority of the managers operating within the matrix. Each project organization operates independently. Duplication of effort can easily occur; for example, two projects might be developing the same cost accounting procedure, or functional personnel may be doing similar R&D efforts on different projects.

Both vertical and horizontal communication is a must in a project matrix organization. One of the advantages of the matrix is a rapid response time for problem resolution.

This rapid response generally applies to slow-moving projects where problems occur

within each functional unit. On fast-moving projects, the reaction time can become quite

slow, especially if the problem spans more than one functional unit. This slow reaction time exists because the functional employees assigned to the project do not have the authority to make decisions, allocate functional resources, or change schedules. Only the line managers have this authority. Therefore, in times of crisis, functional managers must be actively brought into the “big picture” and invited to team meetings.

Middleton has listed four additional undesirable results of matrix organizations, results that can affect company capabilities:

● Project priorities and competition for talent may interrupt the stability of the organization and interfere with its long-range interests by upsetting the traditional business of functional organizations.

● Long-range plans may suffer as the company gets more involved in meeting schedules and fulfilling the requirements of temporary projects.

● Shifting people from project to project may disrupt the training of employees and specialists, thereby hindering the growth and development within their fields of specialization.

● Lessons learned on one project may not be communicated to other projects.

Davis and Lawrence have identified nine additional matrix pathologies:

● Power struggles: The horizontal versus vertical hierarchy.

● Anarchy: Formation of organizational islands during periods of stress.

● Groupitis: Confusing the matrix as being synonymous with group decision making.

● Collapse during economic crunch: Flourishing during periods of growth and collapsing during lean times.

● Excessive overhead: How much matrix supervision is actually necessary?

● Decision strangulation: Too many people involved in decision-making.

● Sinking: Pushing the matrix down into the depths of the organization.

● Layering: A matrix within a matrix.

● Navel gazing: Becoming overly involved in the internal relationships of the organization.

The matrix structure therefore becomes a compromise in an attempt to obtain the best of two worlds. In pure product management, technology suffered because there wasn’t a single group for planning and integration. In the pure functional organization, time and schedule were sacrificed. Matrix project management is an attempt to obtain maximum technology and performance in a cost-effective manner and within time and schedule constraints.

We should note that with proper executive-level planning and control, all of the disadvantages can be eliminated. This is the only organizational form where such control is possible. But companies must resist creating more positions in executive management than are actually necessary as this will drive up overhead rates. However, there is a point where the matrix will become mature and fewer people will be required at the top levels of management.

Previously we identified the necessity for the project manager to be able to establish his own policies, procedures, rules, and guidelines. Obviously, with personnel reporting in two directions and to multiple managers, conflicts over administration can easily occur. According to Shannon:

When operating under a matrix management approach, it is obviously extremely important that the authority and responsibility of each manager be clearly defined, understood and accepted by both functional and program people. These relationships need to be spelled out in writing.

It is essential that in the various operating policies, the specific authority of the program direction, and the authority of the functional executive be defined in terms of operational direction.

Most practitioners consider the matrix to be a two-dimensional system where each project represents a potential profit center and each functional department represents a cost center. (This interpretation can also create conflict because functional departments may feel that they no longer have an input into corporate profits.) For large corporations with multiple divisions, the matrix is no longer two-dimensional, but multidimensional.

William C. Goggin has described geographical area and space and time as the third

and fourth dimensions of the Dow Corning matrix:

Geographical areas . . . business development varied widely from area to area, and the profit center and cost-center dimensions could not be carried out everywhere in the same manner. . . . Dow Corning area organizations are patterned after our major U.S. organizations. Although somewhat autonomous in their operation, they subscribe to the overall corporate objectives, operating guidelines, and planning criteria. During the annual planning cycle, for example, there is a mutual exchange of sales, expense, and profit projections between the functional and business managers headquartered in the United States and the area managers around the world. Space and time. . . . A fourth dimension of the organization denotes fluidity and movement through time. . . . The multidimensional organization is far from rigid; it is constantly changing. Unlike centralized or decentralized systems that are too often rooted deep in the

past, the multidimensional organization is geared toward the future: Long-term planning is an inherent part of its operation.

Goggin then went on to describe the advantages that Dow Corning expected to gain from

the multidimensional organization:

● Higher profit generation even in an industry (silicones) price-squeezed by competition. (Much of our favorable profit picture seems due to a better overall understanding and practice of expense controls through the company.)

● Increased competitive ability based on technological innovation and product quality without a sacrifice in profitability.

● Sound, fast decision-making at all levels in the organization, facilitated by stratified but open channels of communications, and by a totally participative working environment.

● A healthy and effective balance of authority among the businesses, functions, and areas.

● Progress in developing short- and long-range planning with the support of all employees.

● Resource allocations that are proportional to expected results.

● More stimulating and effective on-the-job training.

● Accountability that is more closely related to responsibility and authority.

● Results that are visible and measurable.

● More top-management time for long-range planning and less need to become involved in day-to-day operations.

Obviously, the matrix structure is the most complex of all organizational forms.

Grinnell and Apple define four situations where it is most practical to consider a matrix:

● When complex, short-run products are the organization’s primary output.

● When a complicated design calls for both innovation and timely completion.

● When several kinds of sophisticated skills are needed in designing, building, and testing the products—skills then need constant updating and development.

● When a rapidly changing marketplace calls for significant changes in products, perhaps between the time they are conceived and delivered.

Matrix implementation requires:

● Training in matrix operations

● Training in how to maintain open communications

● Training in problem solving

● Compatible reward systems

● Role definitions

An excellent report on when the matrix will and will not work was made by Wintermantel :

● Situational factors conducive to successful matrix applications:

● Similar products produced in common plants but serving quite different markets.

● Different products produced in different plants but serving the same market or

customer and utilizing a common distribution channel.

● Short-cycle contract businesses where each contract is specifically defined and

essentially unrelated to other contracts.

● Complex, rapidly changing business environment which required close multifunctional integration of expertise in response to change.

● Intensive customer focus businesses where customer responsiveness and solution of customer problems is considered critical (and where the assigned matrix manager represents a focal point within the component for the customer).

● A large number of products/projects/programs which are scattered over many points on the maturity curve and where limited resources must be selectively allocated to provide maximum leverage.

● Strong requirement for getting into and out of businesses on a timely and low cost basis. May involve fast buildup and short lead times. Frequent situations where you may want to test entrance into a business arena without massive commitment of resources and with ease of exit assured.

● High technology businesses where scarce state-of-the-art technical talent must be spread over many projects in the proposal/advanced design stage, but where less experienced or highly talented personnel are adequate for detailed design and follow-on work.

● Situations where products are unique and discrete but where technology, facilities, or processes have high commonality, are interchangeable, or are interdependent.

● Situational factors tending toward nonviable matrix applications:

● Single product line or similar products produced in common plants and serving the same market.

● Multiple products produced in several dedicated plants serving different customers and/or utilizing different distribution channels.

● Stable business environment where changes tend to be glacial and relatively predictable.

● Long, high volume runs of a limited number of products utilizing mature technology and processes.

● Little commonality or interdependence in facilities, technology, or processes.

● Situations where only one profit center can be defined and/or small businesses where critical mass considerations are unimportant.

● Businesses following a harvest strategy wherein market share is being consciously relinquished in order to maintain high prices and generate maximum positive cash flow.

● Businesses following a heavy cost take-out strategy where achieving minimum costs is critical.

● Businesses where there is unusual need for rapid decisions, frequently on a sole-source basis, and wherein time is not usually available for integration, negotiation and exploration of a range of action alternatives.

● Heavy geographic dispersion wherein time/distance factors make close interpersonal integration on a face-to-face recurrent basis quite difficult

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.