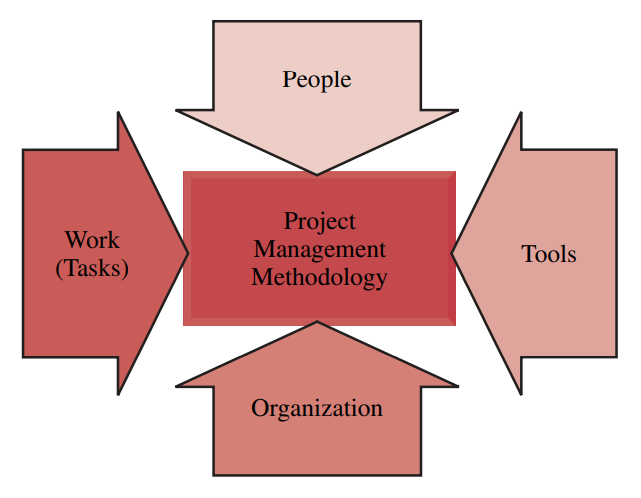

It has often been said that the most difficult projects to manage are those that involve the management of change. Figure 2–26 shows the four basic inputs needed to develop a project management methodology. Each has a “human” side that may require that people change.

Successful development and implementation of a project management methodology

requires:

● Identification of the most common reasons for change in project management

● Identification of the ways to overcome the resistance to change

● Application of the principles of change management to ensure that the desired project management environment will be created and sustained

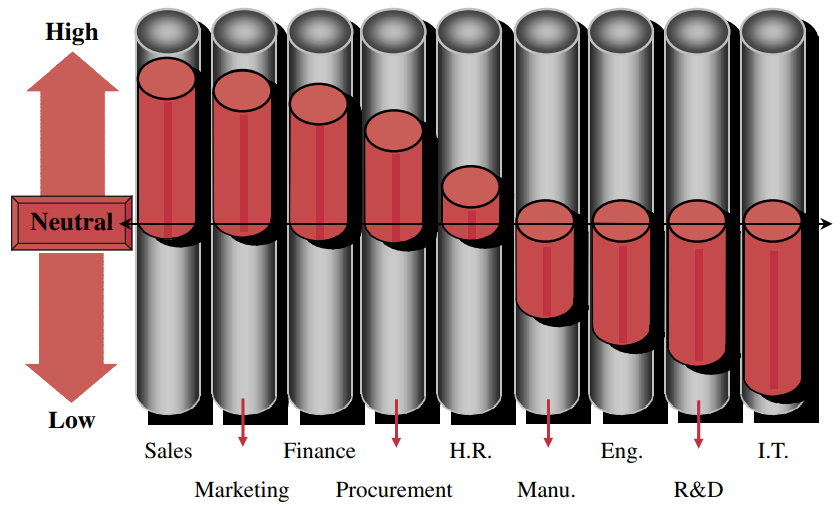

For simplicity’s sake, resistance can be classified as professional resistance and personal resistance to change. Professional resistance occurs when each functional unit as a whole feels threatened by project management. This is shown in Figure 2–27. Examples include:

● Sales: The sales staff’s resistance to change arises from fear that project management will take credit for corporate profits, thus reducing the year-end bonuses for the sales force. Sales personnel fear that project managers may become involved in the sales effort, thus diminishing the power of the sales force.

● Marketing: Marketing people fear that project managers will end up working so closely with customers that project managers may eventually be given some of the marketing and sales functions. This fear is not without merit because customers often want to communicate with the personnel managing the project rather than those who may disappear after the sale is closed.

● Finance (and Accounting): These departments fear that project management will require the development of a project accounting system (such as earned value measurement) that will increase the workload in accounting and finance, and that they will have to perform accounting both horizontally (i.e., in projects) and vertically (i.e., in line groups).

● Procurement: The fear in this group is that a project procurement system will be implemented in parallel with the corporate procurement system, and that the project managers will perform their own procurement, thus bypassing the procurement department.

● Human Resources Management: The HR department may fear that a project management career path ladder will be created, requiring new training programs. This will increase their workloads.

● Manufacturing: Little resistance is found here because, although the manufacturing segment is not project-driven, there are numerous capital installation and maintenance projects which will have required the use of project management.

● Engineering, R&D, and Information Technology: These departments are almost entirely project-driven with very little resistance to project management.

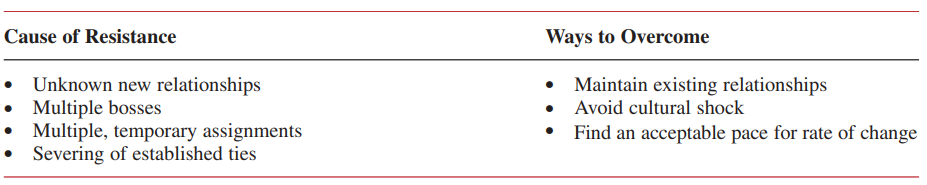

Getting the support of and partnership with functional management can usually overcome the functional resistance. However, the individual resistance is usually more complex and more difficult to overcome. Individual resistance can stem from:

● Potential changes in work habits

● Potential changes in the social groups

● Embedded fears

● Potential changes in the wage and salary administration program

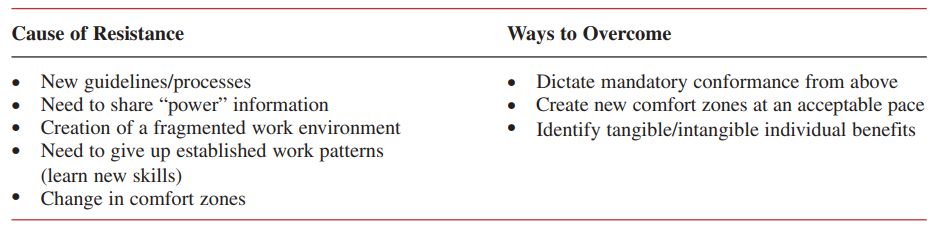

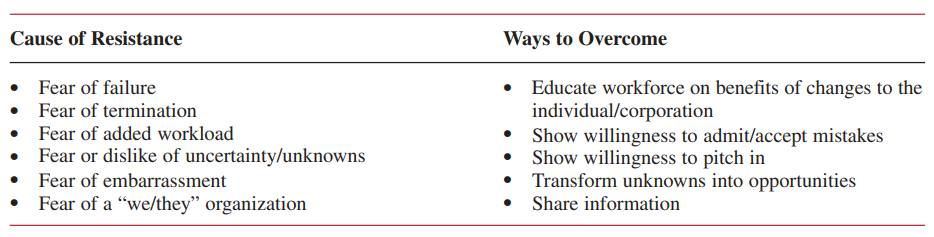

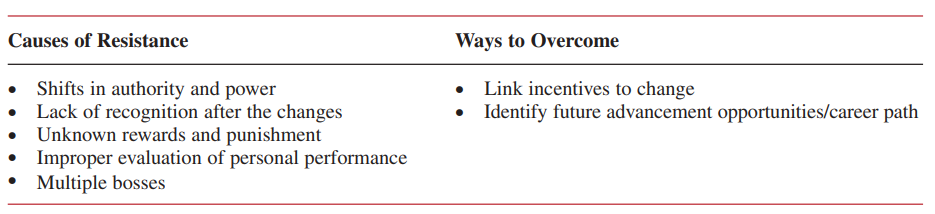

Tables 2–7 through 2–10 show the causes of resistance and possible solutions. Workers tend to seek constancy and often fear that new initiatives will push them outside their comfort zones. Most workers are already pressed for time in their current jobs and fear that new programs will require more time and energy.

Some companies feel compelled to continually undertake new initiatives, and people may become skeptical of these programs, especially if previous initiatives have not been successful. The worst case scenario is when employees are asked to undertake new initiatives, procedures, and processes that they do not understand.

It is imperative that we understand resistance to change. If individuals are happy with their current environment, there will be resistance to change. But what if people are unhappy? There will still be resistance to change unless (1) people believe that the change is possible, and (2) people believe that they will somehow benefit from the change.

Management is the architect of the change process and must develop the appropriate strategies so the organization can change. This is done best by developing a shared understanding with employees by doing the following:

● Explaining the reasons for the change and soliciting feedback

● Explaining the desired outcomes and rationale

● Championing the change process

● Empowering the appropriate individuals to institutionalize the changes

● Investing in training necessary to support the changes

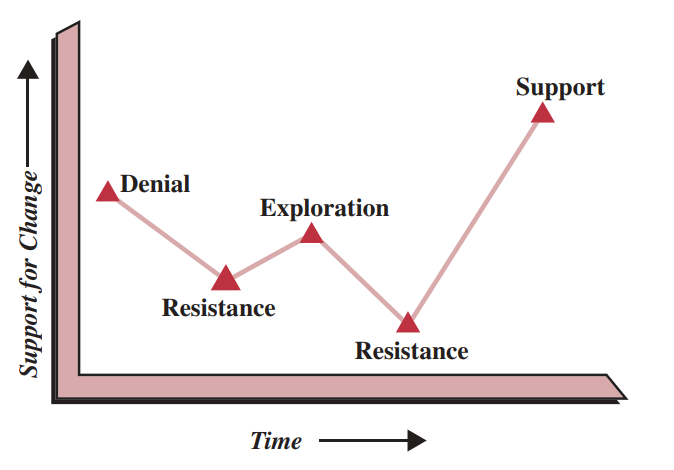

For most companies, the change management process will follow the pattern shown in Figure 2–28. Employees initially refuse to admit the need for change. As management begins pursuing the change, the support for the change diminishes and pockets of resistance crop up. Continuous support for the change by management encourages employees to explore the potential opportunities that will result from the change about to take place.

Unfortunately, this exploration often causes additional negative information to surface, thus reinforcing the resistance to change. As pressure by management increases, and employees begin to recognize the benefits of the proposed change, support begins to grow.

The ideal purpose of change management is to create a superior culture. There are different types of project management cultures based upon the nature of the business, the amount of trust and cooperation, and the competitive environment. Typical types of cultures include:

● Cooperative cultures: These are based upon trust and effective communications, internally and externally.

● Noncooperative cultures: In these cultures, mistrust prevails. Employees worry more about themselves and their personal interests than what’s best for the team, company, or customer.

● Competitive cultures: These cultures force project teams to compete with one another for valuable corporate resources. In these cultures, project managers often demand that the employees demonstrate more loyalty to the project than to their line managers. This can be disastrous when employees are working on many projects at the same time.

● Isolated cultures: These occur when a large organization allows functional units to develop their own project management cultures and can result in a culture-within-a-culture environment.

● Fragmented cultures: These occur when part of the team is geographically separated from the rest of the team. Fragmented cultures also occur on multinational projects, where the home office or corporate team may have a strong culture for project management but the foreign team has no sustainable project management culture.

Cooperative cultures thrive on effective communication, trust, and cooperation. Decisions are based upon the best interest of all of the stakeholders. Executive sponsorship is passive, and very few problems go to the executive levels for resolution. Projects are managed informally and with minimal documentation and few meetings. This culture takes years to achieve and functions well during favorable and unfavorable economic conditions.

Noncooperative cultures are reflections of senior management’s inability to cooperate among themselves and with the workforce. Respect is nonexistent. These cultures are not as successful as a cooperative culture.

Competitive cultures can be healthy in the short term, especially if there is abundant work. Long-term effects are usually not favorable. In one instance, an electronics firm regularly bid on projects that required the cooperation of three departments. Management then implemented the unhealthy decision of allowing each of the three departments to bid on every job. The two “losing” departments would be treated as subcontractors.

Management believed that this competitiveness was healthy. Unfortunately, the long term results were disastrous. The three departments refused to talk to one another and stopped sharing information. In order to get the job done for the price quoted, the departments began outsourcing small amounts of work rather than using the other departments that were more expensive. As more work was outsourced, layoffs occurred. Management then realized the disadvantages of the competitive culture it had fostered.

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.