As companies grew in size, more emphasis was placed on multiple ongoing programs with high-technology requirements. Organizational pitfalls soon appeared, especially in the integration of the flow of work. As management discovered that the critical point in any program is the interface between functional units, the new theories of “interface management” developed.

Because of the interfacing problems, management began searching for innovative methods to coordinate the flow of work between functional units without modification to the existing organizational structure. This coordination was achieved through several integrating mechanisms:

● Rules and procedures

● Planning processes

● Hierarchical referral

● Direct contact

By specifying and documenting management policies and procedures, management attempted to eliminate conflicts between functional departments. Management felt that, even though many of the projects were different, the actions required by the functional personnel were repetitive and predictable. The behavior of the individuals should therefore be easily integrated into the flow of work with minimum communication between individuals or functional groups.

Another means of reducing conflicts and minimizing the need for communication was

detailed planning. Functional representation would be present at all planning, scheduling,

and budget meetings. This method worked best for nonrepetitive tasks and projects.

In the traditional organization, one of the most important responsibilities of upper level management was the resolution of conflicts through “hierarchical referral.” The continuous conflicts and struggle for power between the functional units consistently required that upper-level personnel resolve those problems resulting from situations that were either nonroutine or unpredictable and for which no policies or procedures existed.

The fourth method is direct contact and interactions by the functional managers. The rules and procedures, as well as the planning process method, were designed to minimize ongoing communications between functional groups. The quantity of conflicts that executives had to resolve forced key personnel to spend a great percentage of their time as arbitrators, rather than as managers. To alleviate problems of hierarchical referral, upper-level management requested that all conflicts be resolved at the lowest possible levels. This required that functional managers meet face-to-face to resolve conflicts.

In many organizations, these new methods proved ineffective, primarily because there still existed a need for a focal point for the project to ensure that all activities would be properly integrated.

When the need for project managers was acknowledged, the next logical question was where in the organization to place them. Executives preferred to keep project managers low in the organization. After all, if they reported to someone high up, they would have to be paid more and would pose a continuous threat to management.

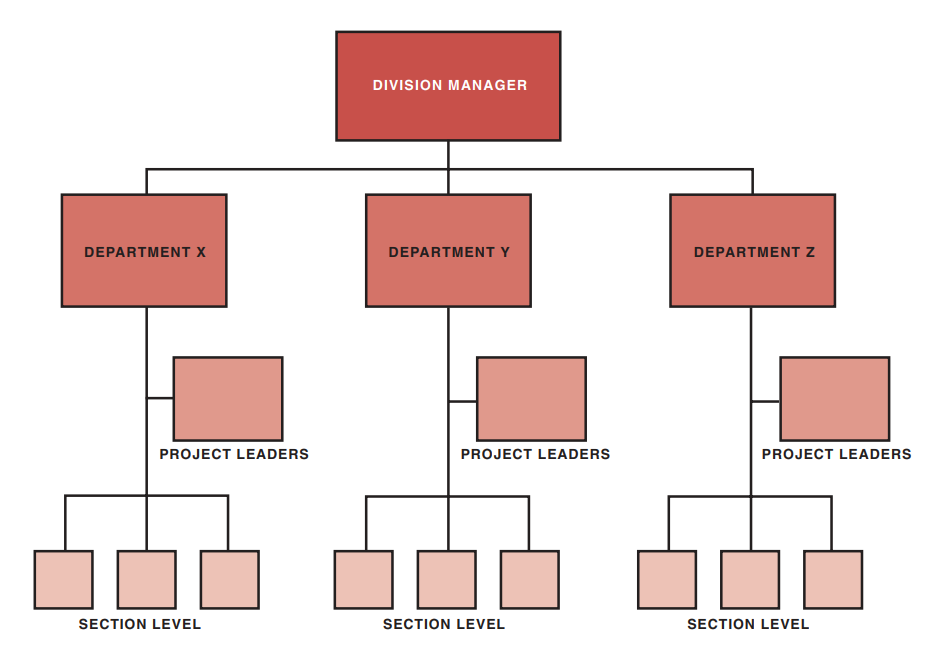

The first attempt to resolve this problem was to develop project leaders or coordinators within each functional department, as shown in Figure 3–2. Section-level personnel were temporarily assigned as project leaders and would return to their former positions at project termination. This is why the term “project leader” is used rather than “project manager,” as the word “manager” implies a permanent relationship. This arrangement proved effective for coordinating and integrating work within one department, provided that the correct project leader was selected. Some employees considered this position an increase in power and status, and conflicts occurred about whether assignments should be based on experience, seniority, or capability. Furthermore, the project leaders had almost no authority, and section-level managers refused to take directions from them, fearing that the project leaders might be next in line for the department manager’s position.

When the activities required efforts that crossed more than one functional boundary, conflicts arose. The project leader in one department did not have the authority to coordinate activities in any other department. Furthermore, the creation of this new position caused internal conflicts within each department. As a result, many employees refused to become dedicated to project management and were anxious to return to their “secure” jobs. Quite often, especially when cross-functional integration was required, the division manager was forced to act as the project manager. If the employee enjoyed the assignment of project leader, he would try to “stretch out” the project as long as possible.

Even though we have criticized this organizational form, it does not mean that it cannot work. Any organizational form will work if the employees want it to work. As an example, a computer manufacturer has a midwestern division with three departments, as in Figure 3–2, and approximately fourteen people per department. When a project comes in, the division manager determines which department will handle most of the work.

Let us say that the work load is 60 percent department X, 30 percent department Y, and 10 percent department Z. Since most of the effort is in department X, the project leader is selected from that department. When the project leader goes into the other two departments to get resources, he will almost always get the resources he wants. This organizational form works in this case because:

● The other department managers know that they may have to supply the project leader on the next activity.

● There are only three functional boundaries or departments involved (i.e., a small organization).

The next step in the evolution of project management was the task force concept. The rationale behind the task force concept was that integration could be achieved if each functional unit placed a representative on the task force. The group could then jointly solve problems as they occurred, provided that budget limitations were still adhered to. Theoretically, decisions could now be made at the lowest possible levels, thus expediting information and reducing, or even eliminating, delay time.

The task force was composed of both part-time and full-time personnel from each department involved. Daily meetings were held to review activities and discuss potential problems. Functional managers soon found that their task force employees were spending more time in unproductive meetings than in performing functional activities. In addition, the nature of the task force position caused many individuals to shift membership within the informal organization. Many functional managers then placed nonqualified and inexperienced individuals on task forces. The result was that the group soon became ineffective because they either did not have the information necessary to make the decisions, or lacked the authority (delegated by the functional managers) to allocate resources and assign work.

Development of the task force concept was a giant step toward conflict resolution:

Work was being accomplished on time, schedules were being maintained, and costs were usually within budget. But integration and coordination were still problems because there were no specified authority relationships or individuals to oversee the entire project through completion.

Attempts were made to overcome this by placing various people in charge of the task force: Functional managers, division heads, and even upper-level management had opportunities to direct task forces. However, without formal project authority relationships, task force members remained loyal to their functional organizations, and when conflicts came about between the project and functional organization, the project always suffered.

Although the task force concept was a step in the right direction, the disadvantages strongly outweighed the advantages. A strength of the approach was that it could be established very rapidly and with very little paperwork. Integration, however, was complicated; work flow was difficult to control; and functional support was difficult to obtain because it was almost always strictly controlled by the functional manager. In addition, task forces were found to be grossly ineffective on long-range projects.

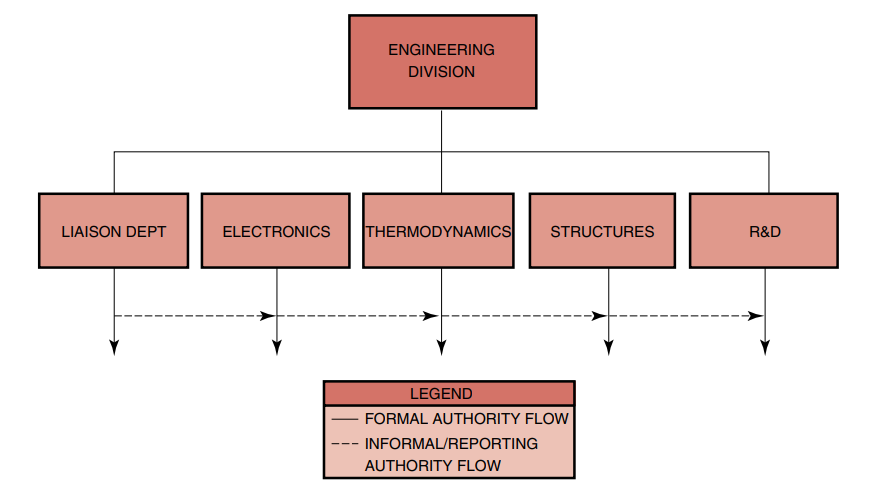

The next step in the evolution of work integration was the establishment of liaison departments, particularly in engineering divisions that perform multiple projects involving a high level of technology (see Figure 3–3). The purpose of the liaison department was to handle transactions between functional units within the (engineering) division. The liaison personnel received their authority through the division head. The liaison department did not actually resolve conflicts. Their prime function was to assure that all departments worked toward the same requirements and goals. Liaison departments are still in existence in many large companies and typically handle engineering changes and design problems.

Unfortunately, the liaison department is simply a scaleup of the project coordinator

within the department. The authority given to the liaison department extends only to the outer boundaries of the division. If a conflict arose between the manufacturing and engineering divisions, for example, it would still be referred to upper management for resolution. Today, liaison departments are synonymous with project engineering and systems engineering departments, and the individuals in these departments have the authority to span the entire organization.

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.