The growth of project management has come about more through necessity than through desire. Its slow growth can be attributed mainly to lack of acceptance of the new management techniques necessary for its successful implementation. An inherent fear of the unknown acted as a deterrent for managers.

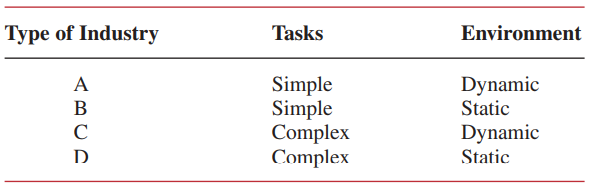

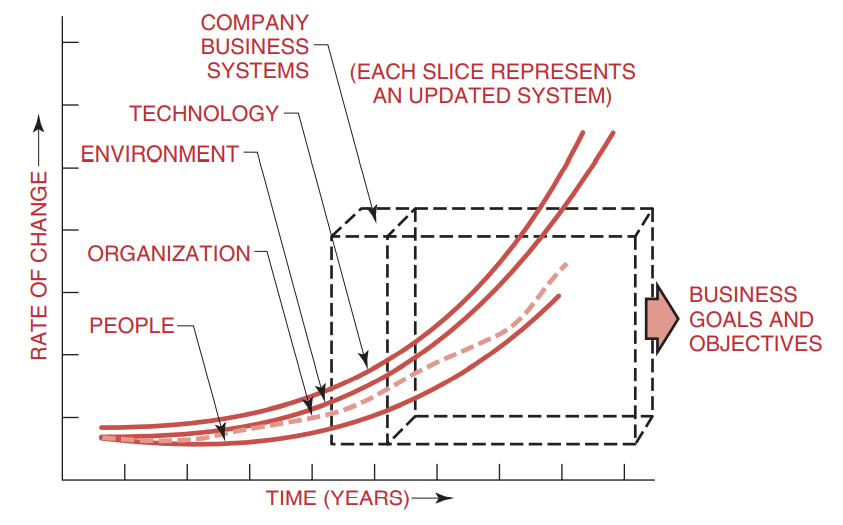

Between the middle and late 1960s, more executives began searching for new management techniques and organizational structures that could be quickly adapted to a changing environment. The table below and Figure 2–1 identify two major variables that executives consider with regard to organizational restructuring.

Almost all type C and most type D industries have project management–related structures. The key variable appears to be task complexity. Companies that have complex tasks and that also operate in a dynamic environment find project management mandatory. Such industries would include aerospace, defense, construction, high-technology engineering, computers, and electronic instrumentation.

Other than aerospace, defense, and construction, the majority of the companies in the 1960s maintained an informal method for managing projects. In informal project management, just as the words imply, the projects were handled on an informal basis whereby the authority of the project manager was minimized.

Most projects were handled by functional managers and stayed in one or two functional lines, and formal communications were either unnecessary or handled informally because of the good working relationships between line managers. Many organizations today, such as low-technology manufacturing, have line managers who have been working side by side for ten or more years. In such situations, informal

project management may be effective on capital equipment or facility development projects.

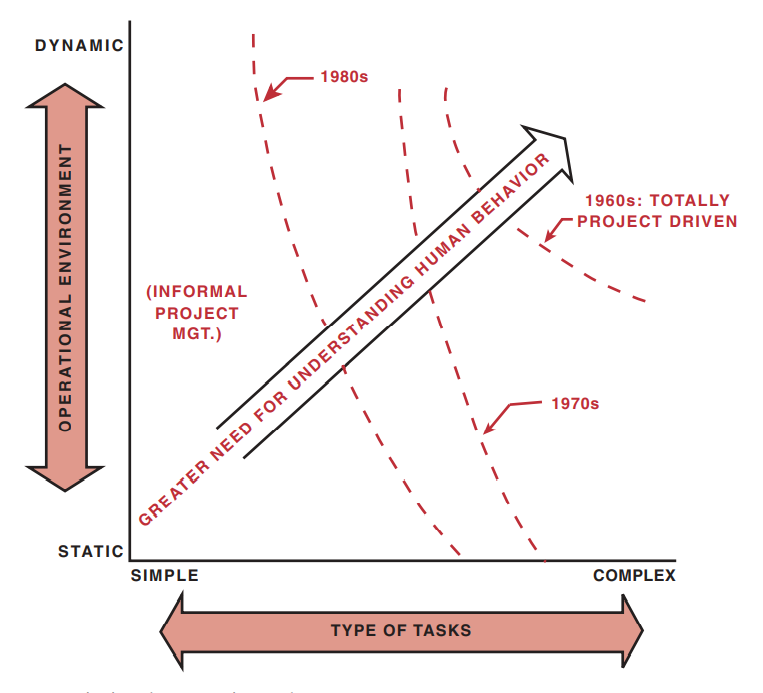

By 1970 and again during the early 1980s, more companies departed from informal project management and restructured to formalize the project management process, mainly because the size and complexity of their activities had grown to a point where they were unmanageable within the current structure. Figure 2–2 shows what happened to one such construction company. The following five questions help determine whether formal project management is necessary:

● Are the jobs complex?

● Are there dynamic environmental considerations?

● Are the constraints tight?

● Are there several activities to be integrated?

● Are there several functional boundaries to be crossed?

If any of these questions are answered yes, then some form of formalized project management may be necessary. It is possible for formalized project management to exist in only one functional department or division, such as for R&D or perhaps just for certain types of projects. Some companies have successfully implemented both formal and informal project management concurrently, but these companies are few and far between. Today we realize that the last two questions may be the most important.

The moral here is that not all industries need project management, and executives must determine whether there is an actual need before making a commitment. Several industries with simple tasks, whether in a static or a dynamic environment, do not need project management. Manufacturing industries with slowly changing technology do not need project management, unless of course they have a requirement for several special projects, such as capital equipment activities, that could interrupt the normal flow of work in the routine manufacturing operations. The slow growth rate and acceptance of project management were related to the fact that the limitations of project management were readily

apparent, yet the advantages were not completely recognizable. Project management requires organizational restructuring. The question, of course, is “How much restructuring?”

Executives have avoided the subject of project management for fear that “revolutionary” changes must be made in the organization. As will be seen in Chapter 3, project management can be achieved with little departure from the existing traditional structure.

Project management restructuring has permitted companies to:

● Accomplish tasks that could not be effectively handled by the traditional structure

● Accomplish onetime activities with minimum disruption of routine business

The second item implies that project management is a “temporary” management structure and, therefore, causes minimum organizational disruption. The major problems identified by those managers who endeavored to adapt to the new system all revolved around conflicts in authority and resources.

Three major problems were identified by Killian:

● Project priorities and competition for talent may interrupt the stability of the organization and interfere with its long-range interests by upsetting the normal business of the functional organization.

● Long-range planning may suffer as the company gets more involved in meeting schedules and fulfilling the requirements of temporary projects.

● Shifting people from project to project may disrupt the training of new employees and specialists. This may hinder their growth and development within their fields of specialization.

Another major concern was that project management required upper-level managers to relinquish some of their authority through delegation to the middle managers. In several situations, middle managers soon occupied the power positions, even more so than upper level managers.

Despite these limitations, there were several driving forces behind the project management approach. According to John Kenneth Galbraith, these forces stem from “the imperatives of technology.” The six imperatives are:

● The time span between project initiation and completion appears to be increasing.

● The capital committed to the project prior to the use of the end item appears to be increasing.

● As technology increases, the commitment of time and money appears to become inflexible.

● Technology requires more and more specialized manpower.

● The inevitable counterpart of specialization is organization.

● The above five “imperatives” identify the necessity for more effective planning, scheduling, and control.

As the driving forces overtook the restraining forces, project management began to mature. Executives began to realize that the approach was in the best interest of the company. Project management, if properly implemented, can make it easier for executives to overcome such internal and external obstacles as:

● Unstable economy

● Shortages

● Soaring costs

● Increased complexity

● Heightened competition

● Technological changes

● Societal concerns

● Consumerism

● Ecology

● Quality of work

Project management may not eliminate these problems, but may make it easier for the company to adapt to a changing environment. If these obstacles are not controlled, the results may be:

● Decreased profits

● Increased manpower needs

● Cost overruns, schedule delays, and penalty payments occurring earlier and earlier

● An inability to cope with new technology

● R&D results too late to benefit existing product lines

● New products introduced into the marketplace too late

● Temptation to make hasty decisions that prove to be costly

● Management insisting on earlier and greater return on investment

● Greater difficulty in establishing on-target objectives in real time

● Problems in relating cost to technical performance and scheduling during the execution of the project

Project management became a necessity for many companies as they expanded into multiple product lines, many of which were dissimilar, and organizational complexities grew. This growth can be attributed to:

● Technology increasing at an astounding rate

● More money invested in R&D

● More information available

● Shortening of project life cycles

To satisfy the requirements imposed by these four factors, management was “forced” into organizational restructuring; the traditional organizational form that had survived for decades was inadequate for integrating activities across functional “empires.” By 1970, the environment began to change rapidly. Companies in aerospace, defense, and construction pioneered in implementing project management, and other industries soon followed, some with great reluctance. NASA and the Department of Defense

“forced” subcontractors into accepting project management. The 1970s also brought much more published data on project management. As an example:

Project teams and task forces will become more common in tackling complexity. There will be more of what some people call temporary management systems as project management systems where the men [and women] who are needed to contribute to the solution meet, make their contribution, and perhaps never become a permanent member of any fixed or permanent management group.

The definition simply states that the purpose of project management is to put together the best possible team to achieve the objective, and, at termination, the team is disbanded. Nowhere in the definition do we see the authority of the project manager or his rank, title, or salary.

Because current organizational structures are unable to accommodate the wide variety of interrelated tasks necessary for successful project completion, the need for project management has become apparent. It is usually first identified by those lower-level and middle managers who find it impossible to control their resources effectively for the diverse activities within their line organization. Quite often middle managers feel the impact of a changing environment more than upper-level executives.

Once the need for change is identified, middle management must convince upper-level management that such a change is actually warranted. If top-level executives cannot recognize the problems with resource control, then project management will not be adopted, at least formally. Informal acceptance, however, is another story.

In 1978, the author received a request from an automobile equipment manufacturer who was considering formal project management. The author was permitted to speak with several middle managers. The following comments were made:

● “Here at ABC Company (a division of XYZ Corporation), we have informal project management. By this, I mean that work flows the same as it would in formal project management except that the authority, responsibility, and accountability are implied rather than rigidly defined. We have been very successful with this structure, especially when you consider that the components we sell cost 30 percent more than our competitors, and that our growth rate has been in excess of 12 percent each year for the past six years. The secret of our success has been our quality and our ability to meet schedule dates.”

● “Our informal structure works well because our department managers do not hide problems. They aren’t afraid to go into another department manager’s office and talk about the problems they’re having controlling resources. Our success is based upon the fact that all of our department managers do this. What’s going to happen if we hire just one or two people who won’t go along with this approach? Will we

be forced to go to formalized project management?”

● “This division is a steppingstone to greatness in our corporation. It seems that all of the middle managers who come to this division get promoted either within the division, to higher management positions in other divisions, or to a higher position at corporate headquarters.”

Next the author conducted two three-day seminars on engineering project management for seventy-five of the lower-, middle-, and upper-level managers. The seminar participants were asked whether they wanted to adopt formal project management. The following concerns were raised by the participants:

● “Will I have more or less power and/or authority?”

● “How will my salary be affected?”

● “Why should I permit a project manager to share the resources in my empire?”

● “Will I get top management visibility?”

Even with these concerns, the majority of the attendees felt that formalized project management would alleviate a lot of their present problems.

Although the middle levels of the organization, where resources are actually controlled on a day-to-day basis, felt positive about project management, convincing the top levels of management was another story. If you were the chief executive officer of this division, earning a six-figure salary, and looking at a growth rate of 12 percent per year for

the last five years, would you “rock the boat” simply because your middle managers want project management?

This example highlights three major points:

● The final decision for the implementation of project management does (and will always) rest with executive management.

● Executives must be willing to listen when middle management identifies a crisis in controlling resources. This is where the need for project management should first appear.

● Executives are paid to look out for the long-range interest of the corporation and should not be swayed by near-term growth rate or profitability.

Today, ABC Company is still doing business the way it was done in the past—with informal project management. The company is a classic example of how informal project management can be made to work successfully. The author agrees with the company executives that, in this case, formal project management is not necessary.

William C. Goggin, board chairman and chief executive officer of Dow Corning, describes a situation in his corporation that was quite different from the one at ABC4:

Although Dow Corning was a healthy corporation in 1967, it showed difficulties that troubled many of us in top management. These symptoms were, and still are, common ones in U.S. business and have been described countless times in reports, audits, articles and speeches. Our symptoms took such forms as:

● Executives did not have adequate financial information and control of their operations.

Marketing managers, for example, did not know how much it cost to produce a product. Prices and margins were set by division managers.

● Cumbersome communications channels existed between key functions, especially manufacturing and marketing.

● In the face of stiffening competition, the corporation remained too internalized in its thinking and organizational structure. It was insufficiently oriented to the outside world.

● Lack of communications between divisions not only created the antithesis of a corporate team effort but also was wasteful of a precious resource—people.

● Long range corporate planning was sporadic and superficial; this was leading to overstaffing, duplicated effort and inefficiency.

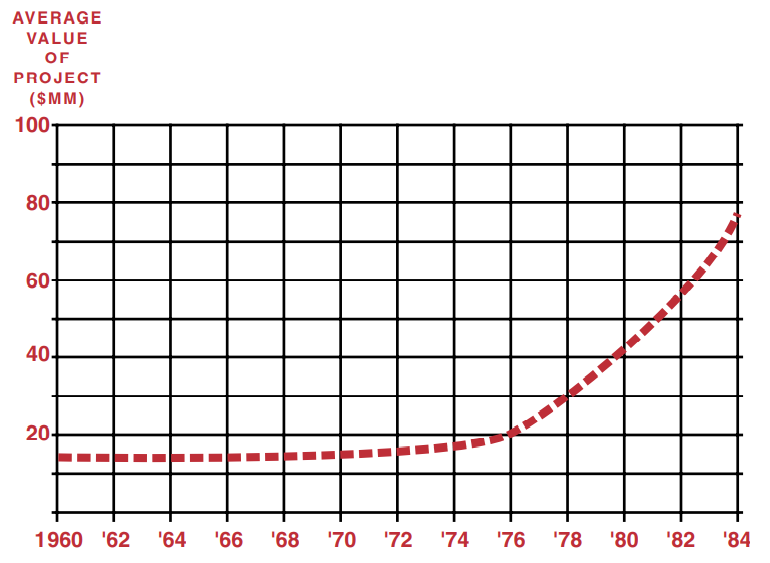

Once the need for project management has been defined, the next logical question is, “How long a conversion period will be necessary before a company can operate in a project management environment?” To answer this question we must first look at Figure 2–3.

Technology, as expected, has the fastest rate of change, and the overall environment of a business must adapt to rapidly changing technology. In an ideal situation, the organizational structure of a company would immediately adapt to the changing environment. In a real situation, this will not be a smooth transition but more like the erratic line shown in Figure 2–3. This erratic line is a trademark or characteristic of the traditional structure. Project management structures, however, can, and often do, adapt to a rapidly changing environment with a relatively smooth transition.

Even though an executive can change the organizational structure with the stroke of a pen, people are responsible for its implementation. However, it can be seen in Figure 2–3 that people have the slowest rate of change. Edicts, documents signed by executives, and training programs will not convince employees that a new organizational form will work. Employees will be convinced only after they see the new system in action, and this takes time.

As a general rule, it often takes two to three years to convert from a traditional structure to a project management structure. The major reason for this is that in a traditional structure the line employee has one, and only one, boss; in a project management structure the employee reports vertically to his line manager and horizontally to every project manager to whose activities he is assigned, either temporarily or full-time. This situation often leads to a culture-shock condition. Employees will perform in a new system because they are directed to do so but will not have confidence in it or become dedicated until they have been involved in several different projects and believe that they can effectively report to

more than one boss.

When an employee is told that he will be working horizontally as well as vertically, his first concern is his take-home pay. Employees always question whether they can be evaluated fairly if they report to several managers during the same time period. One of the major reasons why project management fails is that top-level executives neglect to consider that any organizational change must be explained in terms of the wage and salary administration program. This must occur before change is made. If change comes first, and employees are not convinced that they can be evaluated correctly, they may try to sabotage

the whole effort. From then on, it will probably be a difficult, if not impossible, task to rectify the situation. However, once the employees accept project management and the procedure of reporting in two directions, the company can effectively and efficiently convert from one project management organizational form to another. After all, weren’t most of us educated throughout our childhood on how to report to two bosses—a mother and a father?

Not all companies need two to three years to convert to project management. The ABC Company described earlier would probably have very little trouble in converting because informal project management is well accepted. In the early 1960s, TRW was forced to convert to a project management structure almost overnight. The company was highly successful in this, mainly because of the loyalty and dedication of the employees. The TRW employees were willing to give the system a chance. Any organizational structure, no matter how bad, will work if the employees are willing to make it work. Yet other companies can spend three to five years trying to implement change and fail. The literature describes many cases where project management has failed because:

● There was no need for project management.

● Employees were not informed about how project management should work.

● Executives did not select the appropriate projects or project managers for the first few projects.

● There was no attempt to explain the effect of the project management organizational form on the wage and salary administration program.

● Employees were not convinced that executives totally supported the change.

Some companies (and executives) are forced into project management before they realize what has happened, and chaos ensues. As an example, consider a highly traditional company that purchased its first computer. The company had five divisions: engineering, finance, manufacturing, marketing, and human resources. Not knowing where to put the computer, the chief executive officer created an electronic data processing (EDP) department and placed it under finance and accounting. The executive’s rationale was that since the reason for buying the computer was to eliminate repetitive tasks and the majority of these were in accounting and finance, that was where EDP belonged. The vice president for accounting and finance might not be qualified to manage the EDP department, but that seemed beside the point. The EDP department had a staff of scientific and business computer programmers and systems analysts. The scientific programmers spent almost all their time working in the engineering division writing engineering programs; they had to learn engineering in order to do this. In this company, the engineer did not consider himself to be a computer programmer, but did the computer programmer consider himself to be an engineer?

The company’s policy was that merit and cost-of-living increases were given out in July of each year. This year the average salary increase would be 7 percent. However, the president wanted the increase given according to merit, and not as a flat rate across the board. After long hours of deliberation, it was decided that engineering, manufacturing, and marketing would receive 8 percent raises, and finance and personnel 5.5 percent. After announcing the salary increases, the scientific programmers began to complain because they felt they were doing engineering-type work and should therefore be paid according to the engineering pay scale. Management tried to resolve this problem by giving each division its own computer and personnel. However, this resulted in duplication of effort and inefficient use of personnel. With the rapid advancements in computer technology, management realized the need for timely access to information for executive decision-making. In a rather bold move, executives created a new division called management information systems (MIS). The MIS division now had full control of all computer operations and the EDP personnel had the opportunity to show that they actually contributed to corporate profits. Elevating the computer to the top levels of the organization was a significant step toward project management. Unfortunately, many executives did not fully realize what had happened. Because of the need for a rapid information retrieval system that could integrate data from a variety of line organizations, the MIS personnel soon found that they were working horizontally, not vertically. Today, MIS packages cut across every division of the company. Thus, the project management concept for handling a horizontal flow of work emerged.

With the emergence of data processing project management, executives were forced to find immediate answers to such questions as:

● Can we have project management strictly for data processing projects?

● Should the project manager be the programmer or the user?

● How much authority should be delegated to the project manager, and will this delegated authority cause a shift in the organizational equilibrium?

The answers to these questions have not been and still are not easy to solve. Today, IBM provides its customers with the opportunity to hire IBM as the in-house data processing project management team. This partially eliminates the necessity for establishing internal project management relationships that could easily become permanent.

In TRW Nelson Division,6 data processing project management began with MIS personnel acting as the project leaders. However, after two years, the company felt that the people best qualified to be the project leaders were the technical experts (i.e., users). Therefore, the MIS personnel now act as team members and resource personnel rather than as the project managers.

There are many different types of projects. Each of these projects can have its own organizational form and can operate concurrently with other active projects. This diversity of projects has contributed to the implementation of full project management in several industries.

J. Robert Fluor, chairman, chief executive officer, and president of the Fluor

Corporation, commented on twenty years of operations in a project environment:

The need for flexibility has become apparent since no two projects are ever alike from a project management point of view. There are always differences in technology; in the geographical locations; in the client approach; in the contract terms and conditions; in the schedule; in the financial approach to the project; and in a broad range of international factors, all of which require a different and flexible approach to managing each project. We found the task force concept, with maximum authority and accountability resting with the project manager, to be the most effective means of realizing project objectives. And while

basic project management principles do exist at Fluor, there is no single standard project organization or project procedure yet devised that can be rigidly applied to more than one project.

Today, our company and others and their project managers are being challenged as never before to achieve what earlier would have been classified as “unachievable” project objectives. Major projects often involve the resources of a large number of organizations located on different continents. The efforts of each must be directed and coordinated toward a common set of project objectives of quality performance, cost and time of completion as well as many other considerations.

As project management developed, some essential factors in its successful implementation were recognized. The major factor was the role of the project manager, which became the focal point of integrative responsibility. The need for integrative responsibility was first identified in research and development activities :

Recently, R&D technology has broken down the boundaries that used to exist between industries. Once-stable markets and distribution channels are now in a state of flux. The industrial environment is turbulent and increasingly hard to predict. Many complex facts about markets, production methods, costs and scientific potentials are related to investment decisions.

All of these factors have combined to produce a king-size managerial headache. There are just too many crucial decisions to have them all processed and resolved through regular line hierarchy at the top of the organization. They must be integrated in some other way.

Providing the project manager with integrative responsibility resulted in:

● Total accountability assumed by a single person

● Project rather than functional dedication

● A requirement for coordination across functional interfaces

● Proper utilization of integrated planning and control

Without project management, these four elements have to be accomplished by executives, and it is questionable whether these activities should be part of an executive’s job description. An executive in a Fortune 500 corporation stated that he was spending seventy hours a week acting as an executive and as a project manager, and he did not feel that he was performing either job to the best of his abilities. During a presentation to the staff, the executive stated what he expected of the organization after project management implementation:

● Push decision-making down in the organization

● Eliminate the need for committee solutions

● Trust the decisions of peers

Those executives who chose to accept project management soon found the advantages

of the new technique:

● Easy adaptation to an ever-changing environment

● Ability to handle a multidisciplinary activity within a specified period of time

● Horizontal as well as vertical work flow

● Better orientation toward customer problems

● Easier identification of activity responsibilities

● A multidisciplinary decision-making process

● Innovation in organizational design

Source : Project management A system approach to planning, scheduling and controlling [EIGHTH EDITION] By HAROLD KERZNER, Ph.D.